What Is Alzheimer’s Disease? Definition, Causes, and Progression

Alzheimer’s disease is more than just forgetting where you left your keys. It is a progressive, irreversible neurological disorder that erodes memory and cognitive function, fundamentally altering a person’s identity and ability to function independently. As the most common cause of dementia among older adults, understanding the full Alzheimer’s disease definition requires looking beyond a simple medical term to grasp its profound impact on brain cells, daily life, and the millions of families it touches. This complex condition involves the buildup of abnormal proteins in the brain, leading to the death of neurons and the subsequent loss of vital mental capacities, from recall to reasoning. With no current cure, comprehending its mechanisms, stages, and the difference between normal aging and disease is the critical first step for patients, caregivers, and anyone planning for long-term health.

The Foundational Definition of Alzheimer’s Disease

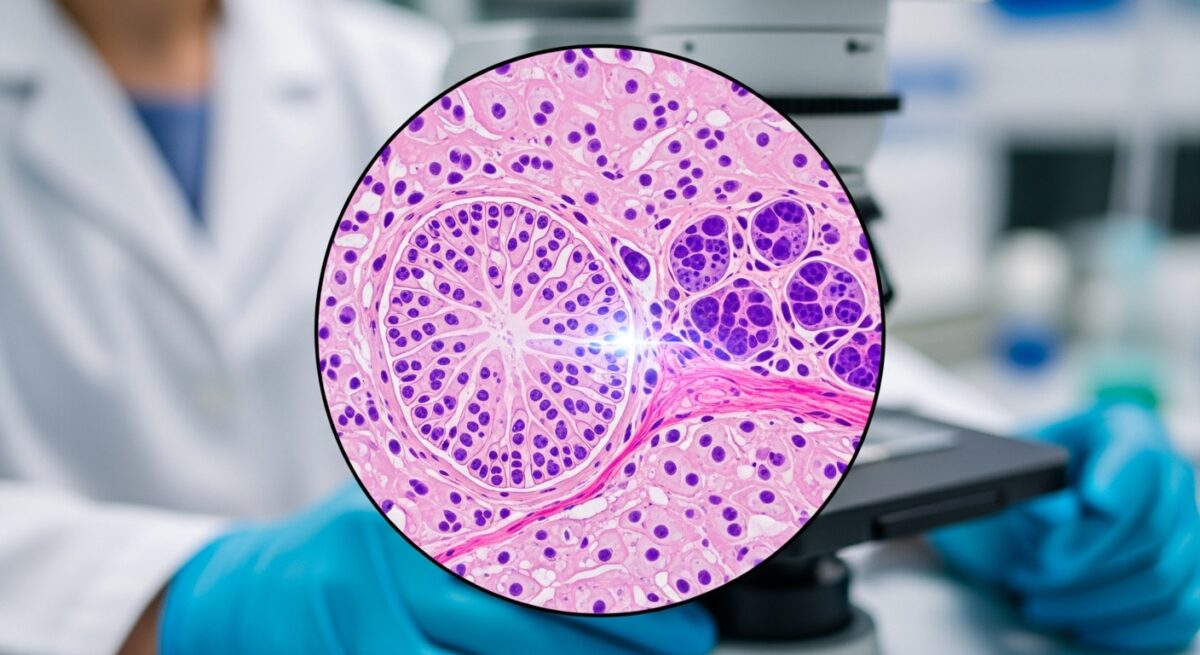

At its core, the Alzheimer’s disease definition describes a specific, degenerative brain disease. It is characterized by a distinct pathology: the accumulation of two abnormal protein structures in the brain, known as amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Amyloid plaques are sticky clumps of protein fragments that build up between nerve cells, while tangles are twisted fibers of a protein called tau that form inside cells. These pathological hallmarks disrupt communication between neurons, trigger inflammation, and ultimately cause widespread brain cell death, leading to the brain shrinkage (atrophy) visible in advanced imaging scans. This biological process distinguishes Alzheimer’s from other forms of dementia, such as vascular dementia or Lewy body dementia, which have different underlying causes and progression patterns. The disease is named after Dr. Alois Alzheimer, who first described the condition in 1906 after observing these abnormal brain changes in a patient with profound memory loss and unpredictable behavior.

Causes and Risk Factors: More Than Just Genetics

The precise cause of Alzheimer’s is not fully understood, but it is widely accepted to result from a combination of genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors that affect the brain over decades. Age is the single greatest known risk factor. The likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s doubles approximately every five years after age 65. Family history and genetics also play a role. Having a first-degree relative with the disease increases risk, and specific genes, like the apolipoprotein E (APOE) e4 allele, are associated with higher susceptibility. However, it is crucial to note that inheriting a risk gene does not guarantee a person will develop the disease, just as its absence does not grant immunity.

Researchers are increasingly focused on modifiable risk factors. Evidence suggests that conditions affecting heart health may also impact brain health. This concept, often called the “heart-head connection,” links cardiovascular risk factors to an increased risk of cognitive decline. Key modifiable factors include:

- Cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol, which can impair blood flow to the brain.

- Poorly managed type 2 diabetes, which can damage blood vessels.

- Physical inactivity and a sedentary lifestyle.

- Smoking and excessive alcohol consumption.

- An unhealthy diet low in fruits and vegetables.

- Social isolation and lack of cognitive engagement.

- Traumatic brain injury, particularly repeated injuries.

This list highlights that while some risk is non-negotiable, proactive management of overall health may help reduce risk or delay onset for some individuals.

Recognizing the Symptoms and Stages of Progression

Alzheimer’s disease symptoms extend far beyond memory lapses. The disease typically manifests gradually and worsens over several years. Early signs often involve subtle changes in thinking and reasoning that are initially mistaken for normal aging or stress. A person may have trouble finding the right word, lose track of dates, or repeatedly ask the same questions. As the disease progresses, these cognitive deficits become more pronounced and interfere with work, social activities, and hobbies.

The progression of Alzheimer’s is commonly described in three broad stages: mild (early-stage), moderate (middle-stage), and severe (late-stage). Understanding the specific characteristics of these stages is vital for caregivers to anticipate needs and provide appropriate support. For a detailed breakdown of the clinical and functional changes in each phase, you can refer to our comprehensive resource on the three stages of Alzheimer’s disease. In mild Alzheimer’s, individuals may still function independently but experience noticeable memory gaps, especially for recent events or conversations. They may struggle with problem-solving, complex tasks, and organizing thoughts. In moderate Alzheimer’s, damage spreads to areas of the brain controlling language, reasoning, sensory processing, and conscious thought. Symptoms become more severe, including significant memory loss (even of personal history), confusion about time and place, increased risk of wandering, and changes in personality, such as paranoia or compulsive behavior. Severe, or late-stage Alzheimer’s, involves a near-total loss of the ability to communicate coherently or care for oneself. Individuals require full-time assistance with daily activities. The brain’s physical changes eventually impair physical functions, such as swallowing, balance, and bowel and bladder control.

Diagnosis and the Importance of Early Detection

There is no single test for Alzheimer’s disease. A diagnosis involves a comprehensive evaluation to rule out other potential causes of dementia symptoms, such as vitamin deficiencies, thyroid problems, or medication side effects. The diagnostic process typically includes a detailed medical history, mental status testing to assess memory and thinking skills, physical and neurological exams, and interviews with family members about changes in behavior and abilities. Brain imaging, like MRI or CT scans, is used to check for evidence of other issues (e.g., stroke, tumor) and to look for patterns of brain shrinkage consistent with Alzheimer’s. In recent years, advances in biomarker testing, including PET scans and cerebrospinal fluid analysis, can detect amyloid and tau proteins in living patients, allowing for a more precise biological diagnosis, though these tests are not yet universally available.

Obtaining an early and accurate diagnosis is critically important. It allows individuals to participate in planning for their future care, explore treatment options that may temporarily improve symptoms, and potentially enroll in clinical trials. For families, it provides a framework for understanding the changes they are witnessing and a starting point for accessing support services and resources.

Current Treatments and the Outlook for a Cure

While there is no cure for Alzheimer’s, several treatment approaches aim to manage symptoms, improve quality of life, and slow disease progression for a limited time. Medications are central to current management. Cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine) are prescribed for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s. They work by boosting levels of a chemical messenger involved in memory and judgment. Memantine, an NMDA receptor antagonist, is used for moderate to severe Alzheimer’s to regulate glutamate, another brain chemical involved in information processing. These drugs do not stop the disease but can help manage cognitive symptoms for a period.

Non-drug therapies are equally essential. Cognitive stimulation, structured routines, physical activity tailored to ability, and nutritional support all contribute to maintaining function and managing behavioral symptoms. Creating a safe, supportive environment and effective communication strategies are pillars of daily care. The landscape of Alzheimer’s treatment is evolving rapidly. Recent years have seen the controversial approval of the first drugs designed to target and remove amyloid plaques from the brain (aducanumab, lecanemab). These represent a shift toward disease-modifying therapies that address the underlying biology, not just the symptoms. Their long-term benefits and risks are still being studied, but they mark a significant, albeit incremental, step forward. A robust pipeline of research continues to explore other targets, including tau protein, inflammation, and metabolic support for brain cells.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Alzheimer’s disease hereditary?

Most cases of Alzheimer’s are “sporadic,” meaning they occur in people with no obvious family history. However, a family history does increase risk. A very small percentage of cases (less than 1%) are caused by specific deterministic genetic mutations, which almost guarantee an early-onset form of the disease.

What is the difference between dementia and Alzheimer’s?

Dementia is an umbrella term for a set of symptoms affecting memory, thinking, and social abilities severely enough to interfere with daily life. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common specific cause of dementia, accounting for 60-80% of cases. All Alzheimer’s patients have dementia, but not all dementia is due to Alzheimer’s.

Can lifestyle changes prevent Alzheimer’s?

While no strategy guarantees prevention, a growing body of evidence suggests that a heart-healthy lifestyle may help reduce risk. This includes regular physical exercise, a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains (like the MIND or Mediterranean diet), managing cardiovascular risk factors, staying socially and mentally active, and avoiding smoking and head injuries.

How long do people live with Alzheimer’s disease?

On average, a person lives 4 to 8 years after diagnosis, but survival can range from 3 to 20 years, depending on age at diagnosis, other health conditions, and the individual’s overall health. The disease progression varies significantly from person to person.

Are there resources for caregivers?

Yes. Caregiving for someone with Alzheimer’s is demanding. Support is available through organizations like the Alzheimer’s Association, which offers a 24/7 helpline, local support groups, educational workshops, and online resources. Respite care services can also provide temporary relief for caregivers.

Grasping the full Alzheimer’s disease definition is the foundation for empathy, effective care, and informed advocacy. It moves us from seeing it as a simple label for memory loss to understanding it as a complex, multi-stage neurological disease with profound personal and societal implications. While the journey is undeniably challenging, knowledge empowers individuals and families to seek timely diagnosis, access current treatments and support, and plan for the future with greater clarity. Ongoing research continues to illuminate the mysteries of the brain, offering hope for more effective interventions and, ultimately, a world without Alzheimer’s.

To discuss early evaluation or new treatment options, contact 📞833-203-6742 or learn more at Learn About Treatment Options.