What Causes Alzheimer’s Disease: A Deep Dive into Risk Factors

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurological disorder that stands as the most common cause of dementia, impacting millions of individuals and their families worldwide. While memory loss is its most recognizable hallmark, the condition involves a far more complex and devastating decline in cognitive function. Understanding what causes Alzheimer’s disease is not a matter of identifying a single culprit, but rather unraveling a tangled web of biological processes, genetic predispositions, and lifestyle influences. The quest for answers drives research forward, offering hope for future prevention and treatment strategies. This exploration moves beyond symptoms to examine the foundational changes in the brain that lead to this challenging condition.

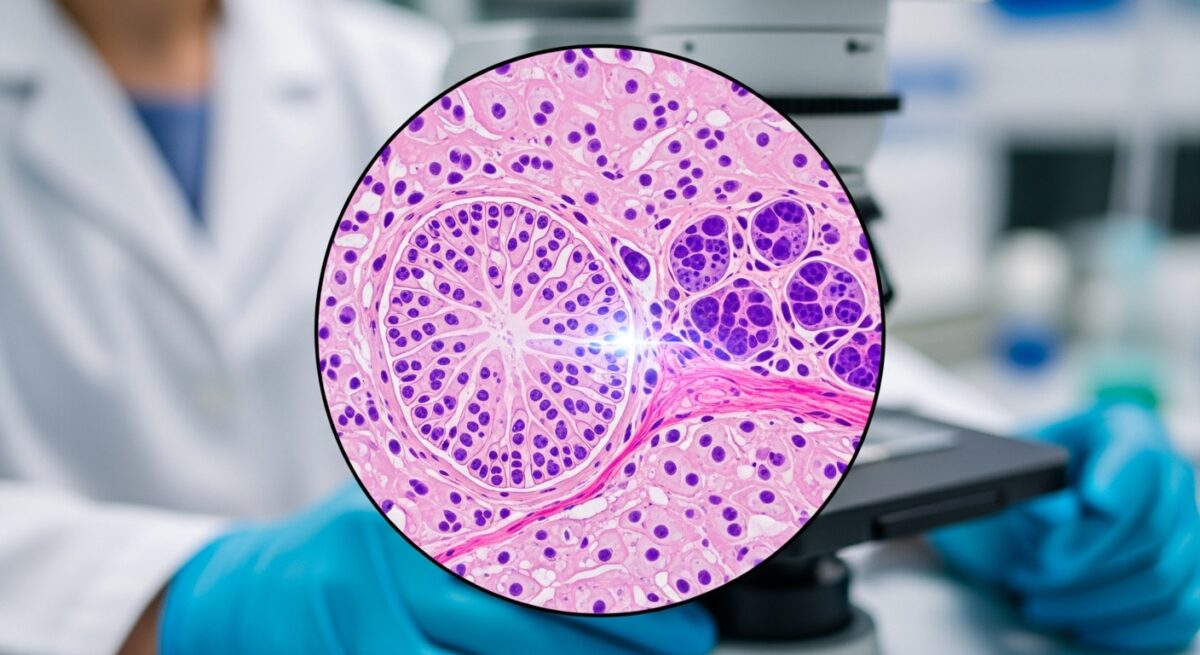

The Hallmarks of Alzheimer’s Pathology in the Brain

At its core, Alzheimer’s disease is defined by specific, observable changes in brain tissue that disrupt communication between neurons and eventually lead to their death. These pathological features are present in characteristic patterns, particularly in regions vital for memory, like the hippocampus, before spreading to other areas. The two primary physical hallmarks are amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. While these structures are the definitive signs of Alzheimer’s, their precise role, whether as direct causes or consequential bystanders, remains a central question in neuroscience. It is the accumulation of these abnormalities that correlates with the progressive symptoms experienced by patients.

Amyloid plaques are dense, insoluble deposits that build up in the spaces between nerve cells. They are primarily composed of a protein fragment called beta-amyloid. In a healthy brain, these protein fragments are broken down and eliminated. In Alzheimer’s, however, the fragments clump together, forming hard, insoluble plaques that are thought to interfere with cell-to-cell signaling and may trigger inflammatory responses that damage neurons. The “amyloid cascade hypothesis” has long been a dominant theory, suggesting that the accumulation of beta-amyloid is the initiating event that sets off a chain reaction leading to widespread neuronal dysfunction and the other hallmark of the disease, tangles.

Neurofibrillary tangles, in contrast, are found inside the neurons themselves. They consist of twisted fibers of a protein called tau. In healthy neurons, tau proteins help stabilize the internal microtubule system, which acts like a transport network for nutrients and essential molecules. In Alzheimer’s, tau proteins become chemically altered, detach from the microtubules, and stick to other tau molecules, forming threads that eventually tangle into insoluble structures. This collapse of the transport system leads to a failure in synaptic communication between neurons and, ultimately, cell death. The spread of tau pathology through the brain closely correlates with the progression of cognitive decline.

Genetic and Inherited Risk Factors

Genetics play a significant, multifaceted role in determining an individual’s risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers categorize this influence into two groups: deterministic genes that directly cause a rare, early-onset form of the disease, and risk genes that increase the likelihood of developing the more common late-onset form. Understanding this distinction is crucial for both families and researchers. While family history is a known risk factor, it does not guarantee one will develop the disease, highlighting the complex interplay between inherited traits and other influences.

Deterministic genes are responsible for familial Alzheimer’s disease, which accounts for less than 1% of all cases and typically manifests before age 65, sometimes as early as one’s 30s or 40s. Mutations in three genes (APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2) are known to cause this inherited form. If a parent carries one of these genetic mutations, a child has a 50% chance of inheriting it, and those who do inherit it will almost certainly develop the disease. The study of these genes has been invaluable to research, as they all relate to the production or processing of beta-amyloid peptide, reinforcing the central role of amyloid in the disease process.

For the vast majority of late-onset Alzheimer’s cases, the genetic link is more subtle. The most significant known genetic risk factor is the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene on chromosome 19. Everyone inherits one form (allele) of APOE (e2, e3, or e4) from each parent. The APOE e4 allele increases risk and may lower the age of onset. Inheriting one copy of e4 from a parent increases risk; inheriting two copies further elevates it. However, carrying the e4 allele does not mean Alzheimer’s is inevitable, and many people with the disease do not carry this allele. Other risk genes have been identified through large genome-wide studies, each contributing a small increase in overall risk, suggesting a polygenic basis for the disease.

Lifestyle, Health, and Environmental Influences

While genetics load the gun, it is often lifestyle and environmental factors that pull the trigger. A substantial body of evidence indicates that modifiable risk factors throughout a person’s life can significantly influence the likelihood of developing cognitive decline. These factors often relate to overall cardiovascular and metabolic health, underscoring the profound connection between a healthy heart and a healthy brain. Making informed choices in these areas represents the most actionable strategy for risk reduction currently available.

Cardiovascular health is tightly linked to brain health. Conditions that damage the heart and blood vessels can also impair blood flow to the brain and contribute to pathology. Key risk factors include:

- Hypertension (High Blood Pressure): Particularly in midlife, hypertension can damage delicate blood vessels in the brain, reducing its resilience.

- Heart Disease and Stroke: These conditions directly affect cerebral blood flow and can cause vascular damage that compounds Alzheimer’s pathology.

- Diabetes and Insulin Resistance: Type 2 diabetes impairs the body’s ability to use insulin and sugar, which can lead to inflammation and may interfere with the brain’s energy metabolism and amyloid clearance.

- High Cholesterol: Elevated levels, especially in midlife, may contribute to vascular damage and beta-amyloid buildup.

Following this list, it’s clear that managing these conditions through diet, exercise, and medication is a critical component of brain health. Furthermore, other modifiable factors play a substantial role. Traumatic brain injury (TBI), particularly repeated injuries, is a strong risk factor, prompting increased safety measures in sports and other activities. Chronic sleep disturbances may impair the brain’s glymphatic system, a waste-clearance process that is most active during sleep and helps remove beta-amyloid. Social isolation and a lack of cognitive engagement in later life are also associated with higher risk, while sustained intellectual and social activity appears to build cognitive reserve, helping the brain compensate for pathology. For a comprehensive look at managing these risks and supporting those affected, our guide on Alzheimer’s disease treatment options and support strategies provides valuable next steps.

The Role of Inflammation and Cellular Processes

Beyond plaques and tangles, scientists are increasingly focused on the role of chronic inflammation and fundamental cellular dysfunctions in Alzheimer’s progression. The brain’s immune cells, called microglia, are tasked with clearing debris, including beta-amyloid plaques and dead neurons. In Alzheimer’s, however, this process seems to go awry. Microglia may become overactivated or dysfunctional, failing to clear plaques efficiently while simultaneously releasing inflammatory chemicals (cytokines) that can damage healthy neurons. This creates a vicious cycle of inflammation and neuronal injury that propels the disease forward.

Other critical cellular processes are also impaired. Mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cell, become less efficient at producing energy, leading to neuronal stress. The brain’s ability to manage oxidative stress, caused by an imbalance of free radicals and antioxidants, also declines with age and is exacerbated in Alzheimer’s, leading to damage of cellular components. Additionally, problems with the brain’s vascular system, including a breakdown of the blood-brain barrier (a network of blood vessels and tissue that protects the brain), may allow harmful substances to enter or hinder the removal of toxins. These interconnected pathways suggest that effective future treatments may need to address multiple biological systems simultaneously.

Age, Sex, and Other Demographic Factors

The single greatest risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease is advancing age. The prevalence of the condition doubles approximately every five years after age 65. This is likely due to the cumulative effect of multiple pathological processes over decades, combined with the brain’s decreasing ability to repair itself. However, it is critical to note that Alzheimer’s is not a normal part of aging. Most older adults do not develop the disease, indicating that age enables the pathology but is not its sole cause.

Sex is another significant demographic factor. Nearly two-thirds of Americans with Alzheimer’s are women. The reasons for this disparity are not fully understood but are likely multifactorial. Longer life expectancy in women accounts for some of the difference, as age is the primary risk factor. However, biological factors may also be at play, including hormonal changes after menopause, such as the decline in estrogen, which has neuroprotective properties. There is also ongoing research into whether genetic or immune system differences between sexes contribute to varying risk levels.

Unanswered Questions and Ongoing Research

The landscape of Alzheimer’s research is dynamic, with several compelling questions driving scientific inquiry. One major area of investigation is the precise sequence of events: does amyloid accumulation invariably come first, triggering tau pathology and inflammation, or can other processes initiate the cascade? Related to this is the concept of “resilience,” or why some individuals with significant amyloid and tau pathology in their brains (as observed post-mortem) showed few cognitive symptoms during life. Understanding the factors that confer this cognitive reserve could unlock new preventive strategies.

Researchers are also delving into the potential roles of the gut microbiome, viral infections (like herpes simplex virus), and air pollution as contributing environmental factors. The goal of much current research is not only to find a cure but to develop reliable biomarkers for early detection through blood tests or advanced brain imaging, allowing for intervention long before symptoms appear. The ultimate aim is to move from disease management to true prevention.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Alzheimer’s disease be prevented?

While there is no guaranteed prevention, strong evidence suggests that managing cardiovascular risk factors (like hypertension, diabetes, and obesity), engaging in regular physical and cognitive activity, maintaining social connections, and eating a heart-healthy diet (such as the Mediterranean or MIND diets) can significantly reduce risk or delay onset.

Is Alzheimer’s disease hereditary?

In most cases, it is not directly inherited in a simple pattern. Family history increases risk, but it is not deterministic. The rare early-onset familial form (less than 1% of cases) is strongly inherited. For the common late-onset form, having a first-degree relative with the disease increases one’s risk, but many people with a family history never develop it, and many with the disease have no known family history.

What is the difference between Alzheimer’s disease and dementia?

Dementia is an umbrella term for a set of symptoms involving memory loss and cognitive impairment severe enough to interfere with daily life. Alzheimer’s disease is a specific brain disease and is the most common cause of dementia, accounting for 60-80% of cases. Other causes include vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and frontotemporal dementia.

How does head injury relate to Alzheimer’s risk?

Sustaining a traumatic brain injury (TBI), particularly moderate to severe or repeated mild injuries, is associated with a significantly increased risk of developing dementia and Alzheimer’s pathology later in life. The mechanism is thought to involve acceleration of tau tangle formation and other neurodegenerative processes.

Are there any early warning signs beyond forgetfulness?

Yes. Early symptoms can include difficulty with planning or solving problems, confusion with time or place, trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships, new problems with words in speaking or writing, misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps, decreased or poor judgment, withdrawal from work or social activities, and changes in mood and personality.

Understanding what causes Alzheimer’s disease reveals a condition of immense complexity, where genetics, biology, lifestyle, and environment converge. The absence of a single, simple cause is both a scientific challenge and a source of hope, as it implies there are multiple avenues for intervention and risk reduction. Current knowledge empowers individuals to take proactive steps toward brain health through lifestyle choices, while researchers continue to piece together the pathological puzzle. This ongoing work is essential for developing the effective treatments and preventive measures that will ultimately alter the course of this disease for future generations.

For personalized guidance on care planning and resources for Alzheimer’s disease, call 📞833-203-6742 or visit Understand Staged Care to speak with a specialist.