Understanding the Pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease, the most common cause of dementia, is not a normal part of aging. It is a progressive, irreversible neurological disorder that erodes memory and cognitive function. At its core, the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease involves a complex cascade of biological events within the brain that lead to the death of nerve cells and the breakdown of neural connections. While memory loss is the hallmark symptom, the true story unfolds decades earlier at the microscopic level, driven by the abnormal accumulation of specific proteins and a profound failure of fundamental cellular processes. Understanding this underlying pathology is crucial for grasping the disease’s progression, the challenges of treatment, and the direction of current research aimed at slowing or stopping its devastating course.

The Core Pathology: Amyloid Plaques and Neurofibrillary Tangles

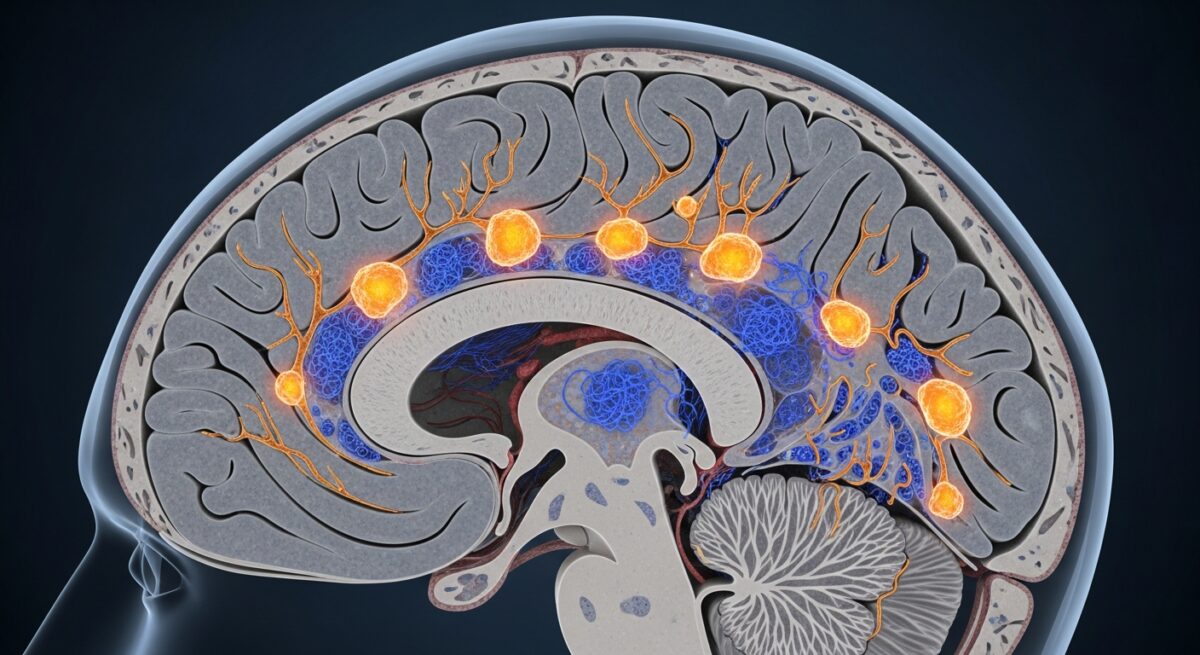

The classical hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease, visible under the microscope in post-mortem brain tissue, are two abnormal structures: amyloid-beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. These are not merely byproducts of the disease, they are considered central drivers of the neuronal damage and synaptic loss that characterize the condition. Their formation represents a failure in the brain’s normal protein management systems, leading to toxic accumulations.

Amyloid-beta plaques are dense, insoluble deposits that build up in the spaces between nerve cells (neurons). They are primarily composed of amyloid-beta peptides, which are fragments snipped from a larger protein called amyloid precursor protein (APP). In a healthy brain, these peptides are typically cleared away. In Alzheimer’s, however, an imbalance between production and clearance leads to an accumulation of these sticky fragments. They clump together into oligomers (small clusters) which are now believed to be particularly toxic, and eventually into the larger plaques. These oligomers and plaques are thought to disrupt cell-to-cell communication at synapses and trigger inflammatory responses from the brain’s immune cells, the microglia.

Neurofibrillary tangles, on the other hand, are found inside the neurons themselves. They are twisted fibers of a protein called tau. In healthy neurons, tau protein binds to and stabilizes microtubules, which are part of the cell’s internal support and transport system. In Alzheimer’s disease, tau becomes hyperphosphorylated, meaning an excessive number of phosphate groups attach to it. This chemical change causes tau to detach from the microtubules and stick to other tau molecules, forming threads that eventually clump into tangles. This process collapses the neuron’s transport system, preventing nutrients and essential materials from moving through the cell, which ultimately leads to cell death. The spread of tau pathology through the brain closely correlates with the progression of cognitive decline. For a deeper look at how these changes manifest in daily life, our guide on recognizing Alzheimer’s disease symptoms details the early signs.

The Cascade of Neurodegeneration and Cellular Dysfunction

The formation of plaques and tangles initiates a destructive domino effect within the brain’s intricate environment. This cascade involves multiple interconnected pathways that collectively lead to widespread neuronal dysfunction and death.

Chronic inflammation is a major component. The brain’s resident immune cells, microglia, are activated in response to amyloid-beta deposits. Initially, this activation is meant to clear the debris. However, in Alzheimer’s, this response becomes chronic and dysfunctional. The overactivated microglia release pro-inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species, chemicals intended to destroy pathogens but which also cause significant collateral damage to nearby neurons and synapses. Astrocytes, another type of glial cell involved in neuronal support, also become reactive and contribute to the inflammatory milieu, further exacerbating the toxic environment.

Synaptic dysfunction and loss represent the most direct correlate of cognitive impairment. Long before neurons die en masse, the connections between them, the synapses, begin to fail. Amyloid-beta oligomers are particularly harmful to synapses, interfering with the signaling mechanisms required for learning and memory. The internal damage from tau tangles also disrupts the transport of vital components to the synapse. As these connections wither, the neural networks that underpin thought, memory, and behavior begin to disintegrate.

Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress are critical downstream events. Neurons are exceptionally energy-demanding cells. Mitochondria, the cellular power plants, become impaired in Alzheimer’s, leading to energy deficits and increased production of damaging free radicals (oxidative stress). This oxidative damage further harms proteins, lipids, and DNA within neurons, pushing them closer to death.

Finally, these combined insults converge on the critical process of programmed cell death, or apoptosis. Neurons, stressed beyond their capacity to survive by inflammation, energy failure, and structural damage, initiate their own self-destruction. The progressive loss of neurons, particularly in brain regions crucial for memory like the hippocampus and later in the cerebral cortex, leads to the characteristic brain atrophy seen in Alzheimer’s disease. This neurodegeneration follows a predictable pattern, which is outlined in our resource on the three stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

Genetic and Risk Factors Influencing Pathophysiology

While the exact triggering event remains elusive, a combination of genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors influences an individual’s risk and potentially the specific trajectory of the disease’s pathophysiology. These factors can affect the onset, rate of progression, and the relative prominence of different pathological features.

From a genetic standpoint, Alzheimer’s is categorized into familial (rare, early-onset) and sporadic (common, late-onset) forms. Familial Alzheimer’s disease, which accounts for less than 5% of cases, is caused by deterministic mutations in one of three genes: APP, Presenilin 1 (PSEN1), or Presenilin 2 (PSEN2). These mutations directly and powerfully drive the overproduction or aggregation of amyloid-beta, leading to symptoms that often appear before age 65.

For the far more common sporadic late-onset Alzheimer’s, the strongest genetic risk factor is the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene, specifically the ε4 allele. The APOE protein is involved in cholesterol transport and, in the brain, amyloid-beta clearance. The APOE ε4 variant is less efficient at clearing amyloid, leading to greater accumulation. Having one ε4 allele increases risk, while having two copies significantly raises it, though it is not deterministic.

Beyond genetics, numerous modifiable risk factors are now understood to shape brain health and resilience against pathological processes. A helpful framework for understanding key contributors includes:

- Vascular Health: Conditions like hypertension, diabetes, and high cholesterol can damage blood vessels in the brain, reducing blood flow and impairing the clearance of toxic proteins.

- Lifestyle Factors: Physical inactivity, poor diet, smoking, and excessive alcohol consumption contribute to systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, which can exacerbate brain pathology.

- Cognitive Reserve: Higher levels of education and lifelong engagement in cognitively stimulating activities may help the brain compensate for pathology by building more robust neural networks, delaying the onset of symptoms.

These risk factors highlight that the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s is not an isolated brain process but is deeply influenced by the body’s overall systemic health. Managing these factors is a cornerstone of current preventive strategies.

Current and Future Therapeutic Approaches Targeting Pathology

The deep understanding of Alzheimer’s pathophysiology has directly guided the development of therapeutic strategies. Historically, treatments like cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine focused on symptom management by modulating neurotransmitter systems affected by neuronal loss. However, the goal of modern research is to develop disease-modifying therapies that interrupt the underlying biological cascade.

A primary focus for decades has been the amyloid hypothesis, leading to drugs designed to reduce amyloid-beta production, prevent its aggregation, or enhance its clearance from the brain. Recently, several monoclonal antibody therapies that target amyloid-beta have received regulatory approval. These drugs, such as lecanemab, work by binding to amyloid-beta to promote its removal by the immune system. They represent a significant shift toward directly addressing a core pathological feature, with clinical trials demonstrating a modest but statistically significant slowing of cognitive decline in the early stages of the disease. It is important to discuss these emerging Alzheimer’s disease treatment options with a healthcare provider to understand their benefits and risks.

Another major frontier is targeting tau pathology. Strategies include developing vaccines or antibodies to block the spread of pathological tau, drugs to inhibit the kinases that hyperphosphorylate tau, and compounds to stabilize microtubules. These approaches aim to halt the intracellular destruction that follows amyloid buildup.

Other innovative avenues aim to mitigate the downstream consequences of plaque and tangle pathology. These include:

- Anti-inflammatory agents: Drugs to modulate the overactive microglial response without compromising the brain’s necessary immune defenses.

- Neuroprotective agents: Compounds designed to enhance neuronal resilience, support mitochondrial function, and reduce oxidative stress.

- Promotion of synaptic health: Strategies to support the growth and maintenance of synapses, aiming to preserve neural networks even in the presence of pathology.

The evolving landscape of Alzheimer’s treatment is complex, and understanding insurance coverage for new therapies is vital. For more information on navigating these options, you can Read full article on related health insurance topics.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s the same for everyone?

While the hallmark features of plaques and tangles are consistent, the relative severity, the brain regions first affected, and the involvement of other co-pathologies (like vascular disease) can vary. This biological heterogeneity contributes to differences in symptoms and disease progression among individuals.

If plaques and tangles are present, does that mean a person will have symptoms?

Not necessarily. The concept of ‘preclinical Alzheimer’s disease’ acknowledges that pathological changes can begin 15-20 years before noticeable symptoms emerge. The brain may compensate for initial damage until a threshold of neuronal and synaptic loss is crossed.

How does understanding pathophysiology help with early diagnosis?

It has led to the development of biomarkers, such as PET scans that visualize amyloid or tau in the living brain, and tests that measure their levels in cerebrospinal fluid. These tools allow for a biological diagnosis earlier in the disease course, even at the preclinical stage, which is crucial for enrolling individuals in prevention trials.

Can lifestyle changes really affect the brain’s pathology?

Growing evidence suggests that managing vascular risk factors and adopting a brain-healthy lifestyle (e.g., regular exercise, a Mediterranean-style diet, cognitive engagement) may reduce inflammation, improve vascular health, and enhance cognitive reserve. This may lower the risk of developing clinical symptoms or delay their onset, potentially by slowing the pathological cascade or increasing the brain’s resilience to it.

What is the biggest challenge in developing drugs based on this pathophysiology?

One major challenge is timing. By the time clinical symptoms appear, significant and likely irreversible neuronal loss has already occurred. Future success likely depends on intervening very early in the pathological process, during the preclinical phase, which requires reliable early detection methods and a willingness to treat asymptomatic individuals.

The journey to unravel the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease has been long and is still ongoing. From the initial identification of plaques and tangles to the current sophisticated understanding of protein misfolding, neuroinflammation, and neuronal network failure, each discovery has illuminated the profound complexity of this condition. This knowledge is more than academic, it is the essential foundation for every hope of effective intervention. It drives the search for early biomarkers, informs the design of targeted therapies, and underscores the importance of holistic brain health strategies. While a cure remains on the horizon, the continued integration of research from the molecular level to the clinical presentation represents our best path toward altering the trajectory of Alzheimer’s disease for future generations.