Understanding Peritoneal Cancer: Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment

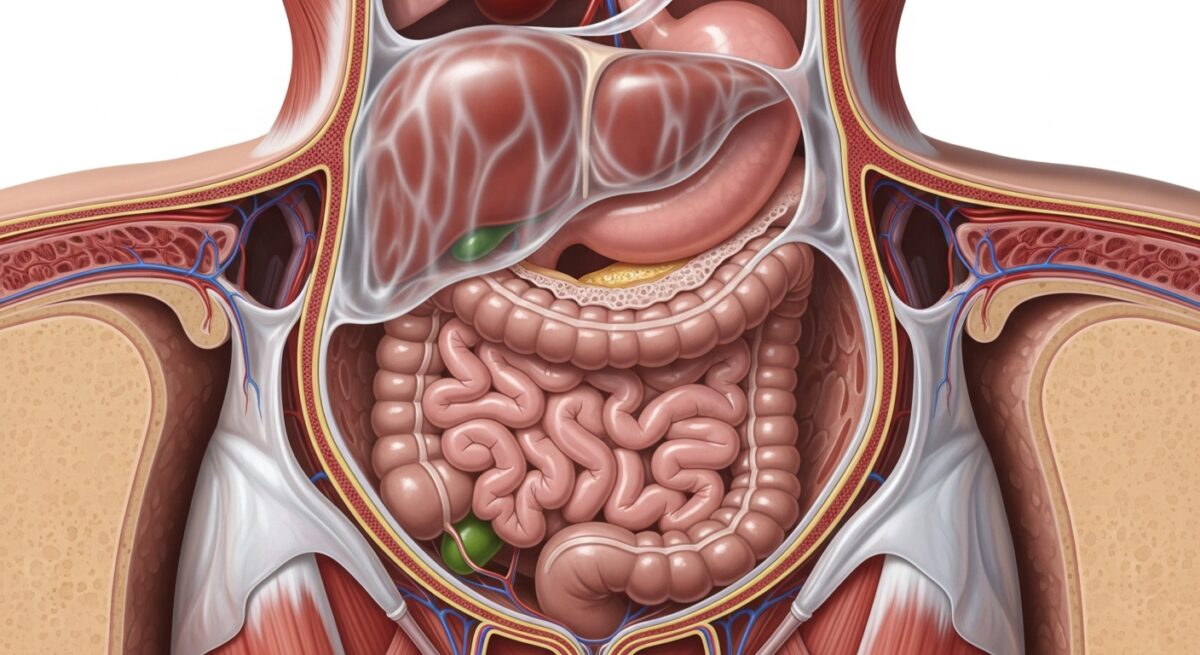

When cancer is found in the lining of the abdominal cavity, it presents a unique and complex medical challenge. This lining, known as the peritoneum, is a thin, supportive membrane that encases abdominal organs and produces lubricating fluid. Cancer affecting this tissue, broadly termed peritoneal cancer, can be a primary disease or, more commonly, a site of spread from other cancers like ovarian, colorectal, or appendiceal cancer. Its location and behavior demand specialized approaches to care, making awareness of its signs and the latest treatment strategies crucial for patients and families navigating this diagnosis.

What Is Peritoneal Cancer?

Peritoneal cancer refers to malignancies that originate in or spread to the peritoneum. Primary peritoneal cancer, where the cancer starts in the peritoneal cells themselves, is rare and behaves similarly to serous ovarian cancer. It is often treated with comparable protocols. The far more frequent scenario is peritoneal carcinomatosis, which is not a separate cancer but a condition where cancer from another organ, such as the stomach, colon, or appendix, metastasizes to the peritoneal surfaces. This spread signifies an advanced stage of the primary disease and significantly influences treatment planning and prognosis. The peritoneum’s extensive surface area can allow cancer cells to disseminate widely within the abdomen, often without immediately spreading to distant organs via the bloodstream.

Understanding the difference between primary and secondary peritoneal cancer is fundamental. Primary peritoneal carcinoma (PPC) is a distinct entity, most commonly seen in women and linked to similar genetic risk factors as ovarian cancer, including BRCA mutations. Secondary peritoneal cancer, or carcinomatosis, is a pattern of metastasis. This distinction guides oncologists in determining the cancer’s origin and selecting the most appropriate therapeutic strategy, which may involve systemic chemotherapy, aggressive surgery, or a combination of both.

Causes and Risk Factors

The exact causes of primary peritoneal cancer are not fully understood, but it shares risk profiles with epithelial ovarian cancer. For secondary peritoneal involvement, the risk is directly tied to the primary cancer. A key mechanism for spread is the shedding of cancer cells from a primary tumor into the abdominal cavity, where they can implant on the peritoneum and grow. Certain cancers have a higher propensity for this type of spread.

Key risk factors and associated conditions include:

- Genetic Mutations: Inherited mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes significantly increase the risk for primary peritoneal cancer and ovarian cancer.

- Personal History of Cancer: A prior diagnosis of colorectal, appendiceal, gastric, pancreatic, or ovarian cancer elevates the risk of peritoneal metastasis.

- Certain Primary Cancers: Appendiceal cancers, particularly mucinous types, and pseudomyxoma peritonei (a related condition) almost exclusively spread within the peritoneum.

- Age and Gender: Primary peritoneal cancer is most frequently diagnosed in postmenopausal women.

While not all cases are preventable, understanding these risks can lead to more vigilant monitoring for individuals with a strong family history or known genetic predisposition. Genetic counseling and testing may be recommended for some patients and families.

Symptoms and Early Signs

Symptoms of peritoneal cancer are often vague and nonspecific in the early stages, leading to delayed diagnosis. They result from the cancer affecting the function of the abdominal cavity. As cancer cells multiply and the peritoneum produces excess fluid (ascites), pressure builds on internal organs.

Common symptoms include abdominal bloating or distension, a feeling of fullness or pressure, changes in bowel habits (such as constipation or diarrhea), indigestion, nausea, loss of appetite, unexplained weight loss, and fatigue. In many cases, persistent and increasing abdominal bloating is the most noticeable complaint. Pain may also be present, ranging from a general dull ache to more localized discomfort. It is critical to consult a healthcare provider if such symptoms are new, persistent, and unexplained, especially for individuals with a known history of abdominal cancers.

Diagnostic Process and Staging

Diagnosing peritoneal cancer involves a multi-step process to confirm the presence of disease and determine its extent. There is no single test; instead, physicians rely on a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging, and tissue analysis. The journey often begins with a detailed medical history and physical exam, where a doctor may detect ascites or abdominal masses.

Imaging studies are crucial. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is the most common initial tool, providing detailed pictures that can show thickening of the peritoneum, the presence of ascites, and possible tumors. In some centers, a specialized PET-CT scan may be used to identify areas of high metabolic activity indicative of cancer spread. Ultimately, a biopsy is required for a definitive diagnosis. This may be obtained via image-guided needle biopsy or, more commonly, through a surgical procedure like laparoscopy, which allows direct visualization of the peritoneum and collection of tissue and fluid samples. Analysis of ascitic fluid (paracentesis) can also reveal cancer cells.

Staging for peritoneal surface malignancy often uses the Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI), a surgical scoring system that quantifies the extent of disease within 13 abdominal regions. This index, along with assessments of the primary tumor and lymph node involvement, helps determine whether a patient is a candidate for aggressive cytoreductive surgery and guides prognosis.

Treatment Options and Advances

Treatment for peritoneal cancer is complex and highly individualized, typically managed by a multidisciplinary team at specialized centers. The approach depends on whether the disease is primary or secondary, the primary cancer type, the volume and distribution of peritoneal disease (PCI score), and the patient’s overall health. The goal may be curative or focused on controlling symptoms and prolonging life.

The most aggressive and potentially curative strategy for limited peritoneal spread from certain cancers (e.g., appendix, colorectal, mesothelioma, some ovarian) involves a two-part procedure: cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). CRS aims to surgically remove all visible tumor deposits from the abdominal cavity. Immediately following, while the patient is still in the operating room, HIPEC is performed. A heated chemotherapy solution is circulated throughout the abdominal cavity for 60 to 90 minutes. The heat enhances the penetration and effectiveness of the chemotherapy in killing microscopic residual cancer cells directly at the site.

For patients who are not candidates for CRS-HIPEC, or for those with primary peritoneal carcinoma, systemic chemotherapy remains the cornerstone of treatment. This involves drugs delivered intravenously to travel throughout the body. Targeted therapies and immunotherapy are also emerging as options for specific cancer types based on genetic markers. Palliative procedures, such as paracentesis to drain ascitic fluid, are essential for managing symptoms and improving quality of life for all patients with advanced disease.

Prognosis and Quality of Life

Prognosis varies widely based on the cancer’s origin, the completeness of surgical removal, and response to systemic therapy. For selected patients who undergo successful complete cytoreduction followed by HIPEC, long-term survival and even cure are possible, particularly with low-grade appendiceal cancers. For others, peritoneal carcinomatosis is managed as a chronic condition. The focus often shifts to maintaining the best possible quality of life through symptom management, nutritional support, and palliative care services.

Managing ascites, bowel obstructions, pain, and fatigue requires a dedicated support team. Nutritional counseling is vital, as cancer and its treatments can severely impact digestion and appetite. Integrating palliative care early in the treatment journey, alongside curative or life-prolonging therapies, has been shown to improve both quality of life and patient satisfaction with care.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is peritoneal cancer the same as stomach or ovarian cancer?

No, it is not the same. Peritoneal cancer is defined by its location: the lining of the abdomen. It can be a primary cancer of that lining, or it can be a spread (metastasis) from a primary cancer that started elsewhere, like the stomach, ovaries, colon, or appendix.

What is the life expectancy for someone with peritoneal carcinomatosis?

Life expectancy is highly variable and depends on the primary cancer type, the extent of spread, the patient’s overall health, and response to treatment. With modern treatments like CRS and HIPEC, some patients with certain cancers can achieve long-term survival. A medical oncologist can provide a more personalized prognosis based on individual circumstances.

Can peritoneal cancer be prevented?

There is no guaranteed prevention. However, for individuals with a very high genetic risk (like BRCA carriers), risk-reducing surgery to remove the ovaries and fallopian tubes can also significantly reduce the risk of primary peritoneal cancer. Managing risk factors for gastrointestinal cancers, like maintaining a healthy diet and getting recommended colon cancer screenings, may reduce the risk of cancers that could spread to the peritoneum.

What are the side effects of HIPEC treatment?

HIPEC is a major surgical procedure. Potential side effects include those associated with major abdominal surgery (infection, bleeding, blood clots) and chemotherapy (kidney toxicity, bone marrow suppression, nausea). Recovery is lengthy, often requiring a hospital stay of one to two weeks or more.

How is ascites managed?

Ascites (abdominal fluid buildup) is managed through dietary changes (reducing salt intake), diuretic medications, and periodic drainage of the fluid via a needle procedure called paracentesis. For recurrent ascites, a permanent catheter may be placed to allow for drainage at home.

Navigating a peritoneal cancer diagnosis requires specialized medical expertise and a strong support network. Advances in surgical techniques and systemic therapies continue to improve outcomes, offering hope and more options for patients. If you or a loved one are facing symptoms or a diagnosis related to the abdominal lining, seeking care from a center with experience in peritoneal surface malignancies is a critical step toward receiving the most comprehensive and effective treatment plan available.