Understanding Papillary Thyroid Cancer: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outlook

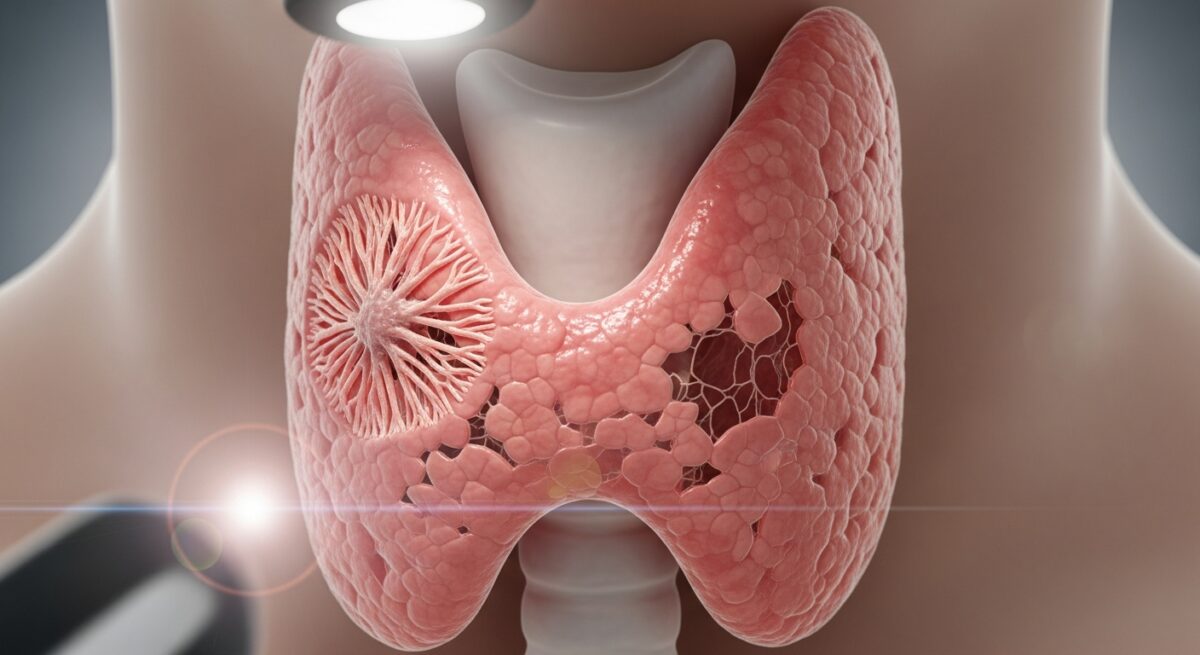

Papillary thyroid cancer is the most common type of thyroid cancer, accounting for roughly 80% of all cases. While a cancer diagnosis is always concerning, this particular form is often highly treatable and carries an excellent prognosis, especially when detected early. It develops from the follicular cells in the thyroid, a butterfly-shaped gland at the base of your neck responsible for regulating metabolism. The term “papillary” refers to the unique finger-like projections, or papillae, that pathologists see when examining the cancer cells under a microscope. This article provides a comprehensive, in-depth look at papillary thyroid cancer, covering its causes, symptoms, diagnostic journey, treatment options, and long-term management to empower patients and their families with knowledge.

What Causes Papillary Thyroid Cancer?

The exact cause of papillary thyroid cancer remains unclear, but researchers have identified several key risk factors. Unlike some cancers with strong lifestyle links, papillary thyroid cancer’s primary known risk factor is exposure to ionizing radiation, particularly during childhood. This includes radiation treatments to the head, neck, or chest (for prior cancers or conditions like acne) and exposure from nuclear fallout or accidents. Genetic factors also play a role. While most cases are sporadic, a family history of thyroid cancer or certain inherited syndromes, such as Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) or Cowden syndrome, increases risk. It is also more frequently diagnosed in women than in men and most commonly appears in people between the ages of 30 and 50, though it can occur at any age.

Recognizing the Signs and Symptoms

Papillary thyroid cancer is often discovered incidentally because it may not cause symptoms in its early stages. It is frequently found during a routine physical exam when a doctor feels a nodule on the thyroid, or during an imaging test like an ultrasound or CT scan performed for another reason. When symptoms do occur, they are typically related to the physical presence of the tumor. The most common sign is a painless lump or swelling in the front of the neck. As the nodule grows, it may lead to other symptoms due to pressure on nearby structures. These can include a persistent hoarseness or voice changes, difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), a sensation of a lump in the throat, neck or throat pain, and sometimes swollen lymph nodes in the neck. It is crucial to note that thyroid nodules are extremely common, and the vast majority are benign. However, any new neck lump or persistent symptom warrants evaluation by a healthcare professional. For a deeper look at potential indicators, our resource on thyroid cancer symptoms and early warning signs provides detailed information.

The Diagnostic Pathway

Diagnosing papillary thyroid cancer involves a stepwise approach to assess a thyroid nodule. The process typically begins with a physical examination of the neck. If a nodule is suspected, the next crucial step is a thyroid ultrasound. This imaging test is painless and uses sound waves to create pictures of the thyroid. It helps determine the nodule’s size, location, and characteristics, such as whether it is solid or fluid-filled (cystic), and if it has features like microcalcifications or irregular borders that are more suspicious for cancer. Based on the ultrasound findings, doctors use standardized criteria (like the TI-RADS system) to decide if a fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy is needed. An FNA biopsy is the definitive test for diagnosis. Using a very thin needle, a doctor extracts cells from the thyroid nodule, sometimes with ultrasound guidance. A pathologist then examines these cells under a microscope. The results generally fall into one of several categories:

- Benign: Non-cancerous. No further action is usually needed, except possibly monitoring.

- Malignant: Cancerous, confirming a diagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer or another type.

- Suspicious for Malignancy: Highly suggestive of cancer, often leading to a surgical recommendation.

- Follicular Neoplasm: Cells look abnormal but are not definitively cancerous; surgery is often required for a final diagnosis.

- Non-diagnostic: The sample did not contain enough cells; the biopsy may need to be repeated.

If cancer is confirmed, additional tests like a CT scan of the neck or chest may be performed to see if the cancer has spread beyond the thyroid, a process known as staging.

Standard Treatment Options and Approaches

Treatment for papillary thyroid cancer is highly effective and typically multimodal, meaning it combines more than one approach. The primary treatment is surgery. The goal of surgery is to remove all cancerous tissue. The type of operation depends on the size of the tumor, whether it is in one or both lobes of the thyroid, and if it has spread to lymph nodes. A lobectomy removes only the affected lobe of the thyroid and is sometimes an option for very small, low-risk cancers confined to one lobe. A total thyroidectomy removes the entire thyroid gland and is the most common surgery for papillary thyroid cancer, especially for tumors larger than 1 cm, those in both lobes, or when there is evidence of spread. During surgery, the surgeon will also often remove and examine nearby central neck lymph nodes to check for cancer spread.

Following a total thyroidectomy, most patients require a subsequent treatment called radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy, or I-131 therapy. Since thyroid cells (both healthy and cancerous) are the only cells in the body that absorb iodine, a radioactive form of iodine can be used to seek out and destroy any remaining thyroid tissue or cancer cells after surgery. Patients swallow a capsule or liquid containing I-131, which circulates through the body. To make this treatment most effective, patients must have high levels of a hormone called Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH), which can be achieved by temporarily stopping thyroid hormone medication (thyroid hormone withdrawal) or by receiving injections of synthetic TSH. After RAI treatment, patients must follow specific radiation safety precautions for a short time. Lifelong thyroid hormone replacement therapy is mandatory after the thyroid is removed. This serves two critical purposes: it replaces the essential hormones your body can no longer produce, and it suppresses TSH to very low levels, as TSH can stimulate the growth of any lingering thyroid cancer cells.

Prognosis, Monitoring, and Living Well After Treatment

The prognosis for papillary thyroid cancer is generally outstanding, with overall survival rates exceeding 98% over 20 years for most patients when treated appropriately. However, long-term monitoring is essential to ensure the cancer does not return (recur). This involves regular follow-up visits with an endocrinologist or oncologist. Monitoring typically includes physical exams, blood tests, and periodic imaging. Key blood tests measure thyroglobulin (a protein made only by thyroid tissue) and thyroglobulin antibodies. After successful treatment, thyroglobulin levels should be very low or undetectable. A rising level can be the first sign of recurrence. Neck ultrasounds are also used regularly to check for any new nodules or abnormal lymph nodes in the neck. While the physical aspects of treatment are paramount, addressing the emotional and practical sides is also crucial. A cancer diagnosis can be stressful, and navigating insurance coverage for surgery, RAI, and lifelong medication is a common concern. Understanding your Medicare Advantage or other health insurance plans is an important step in managing the financial aspects of care.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is papillary thyroid cancer fatal?

For the vast majority of patients, papillary thyroid cancer is not fatal. It is one of the most treatable and survivable cancers, especially when diagnosed early. The long-term survival rate is extremely high, and most people go on to live full, normal lives after treatment.

What are the long-term side effects of treatment?

The most common long-term effect is the need to take thyroid hormone medication (levothyroxine) every day for life. If the parathyroid glands (which control calcium) are damaged during surgery, some patients may need to take calcium and vitamin D supplements. Side effects from RAI are usually temporary, but some people experience dry mouth or changes in taste.

Can I get pregnant after thyroid cancer treatment?

Yes, pregnancy is generally safe and achievable after treatment for papillary thyroid cancer. It requires careful planning and coordination with your endocrinologist and obstetrician to ensure your thyroid hormone levels are optimally managed before and during pregnancy.

How often will I need follow-up appointments?

Follow-up is most frequent in the first few years after treatment, typically every 6 to 12 months. If you remain disease-free for several years, the interval between appointments may be extended. Your doctor will create a personalized surveillance schedule based on your initial risk level.

Does having my thyroid removed affect my weight or energy?

Once your thyroid hormone medication dose is correctly adjusted, your metabolism and energy levels should normalize. Weight gain is not an inevitable result of thyroid removal; it is managed by finding the right hormone dose, maintaining a balanced diet, and regular exercise.

Receiving a diagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer can be a life-altering event, but it is important to remember that this is a disease with a well-established and highly successful treatment roadmap. With appropriate surgery, often followed by radioactive iodine and lifelong thyroid hormone therapy, the outlook is overwhelmingly positive. Ongoing advances in diagnostics, surgical techniques, and risk stratification continue to improve outcomes and personalize care. By partnering with a dedicated medical team, adhering to follow-up protocols, and accessing reliable information, patients can confidently navigate their journey toward long-term health.