Understanding Heart Cancer: Tumors, Symptoms, and Treatment

When you hear the term “heart cancer,” it often sparks confusion and fear. This is because primary malignant tumors of the heart are exceptionally rare, representing less than 0.1% of all cancers diagnosed. The heart is an organ remarkably resistant to developing its own cancerous growths, a fact that offers little comfort to those facing this daunting diagnosis. This article will demystify heart cancer, exploring the types of tumors that can affect the heart, their symptoms, how they are diagnosed and treated, and the critical differences between primary and secondary cancers. Understanding this complex condition is the first step toward navigating its challenges.

What Is Heart Cancer?

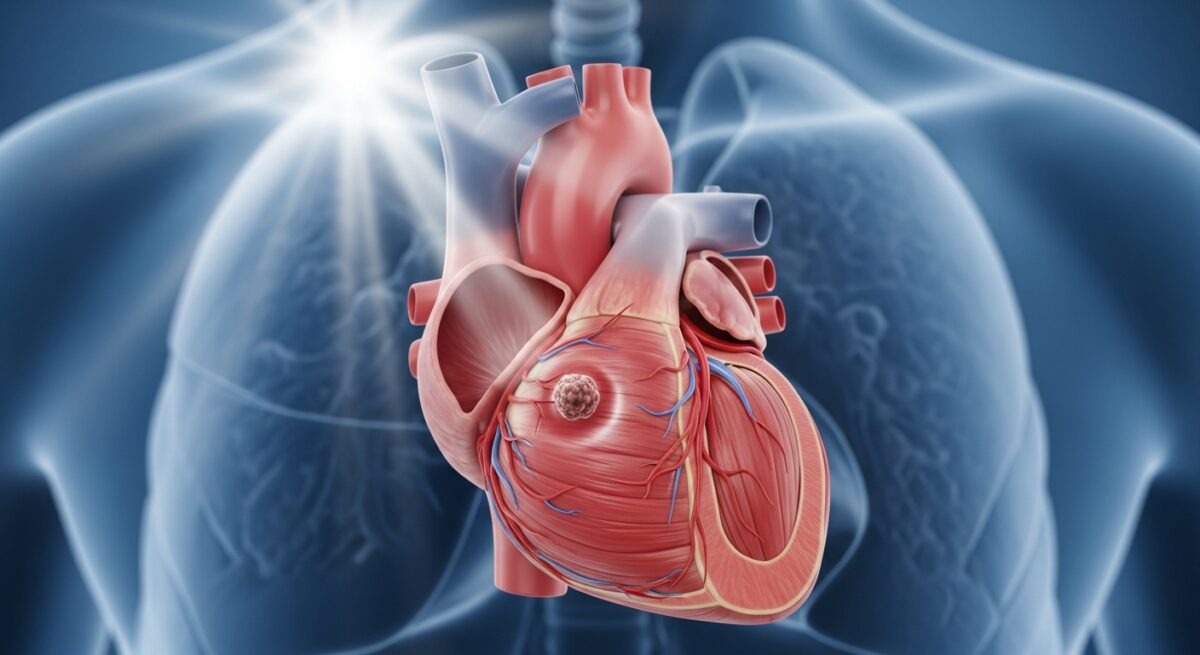

Medically, “heart cancer” typically refers to a primary cardiac tumor, meaning a tumor that originates in the tissues of the heart itself. It is crucial to distinguish this from secondary, or metastatic, cancer, which is far more common. Metastatic heart cancer occurs when cancer cells from another part of the body (such as the lung, breast, or skin) spread through the bloodstream or lymphatic system and attach to the heart. Primary heart cancer is so rare that most cardiologists may never encounter a case in their careers. The most common primary malignant tumor of the heart is a sarcoma, a type of cancer arising from the heart’s soft tissues or blood vessels. Other types include primary cardiac lymphoma and malignant pericardial mesothelioma.

Types of Cardiac Tumors

Cardiac tumors are broadly categorized as benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous). Interestingly, about 75% of primary heart tumors are benign. The most common benign tumor is a myxoma, often found in the left atrium. While benign tumors are not cancerous, they can still be life-threatening by obstructing blood flow, causing arrhythmias, or leading to embolic events (where a piece of the tumor breaks off and travels through the bloodstream). Malignant primary tumors are predominantly sarcomas, which are aggressive and can grow rapidly, invading the heart muscle and surrounding structures. Understanding the specific type is paramount for determining prognosis and treatment.

Primary Malignant Heart Tumors

Angiosarcomas are the most frequent primary malignant heart tumors. They typically arise in the right atrium and are composed of cells that line blood vessels. These tumors are highly aggressive, often metastasizing to the lungs, liver, and brain by the time of diagnosis. Another type, rhabdomyosarcoma, originates from muscle tissue within the heart. Primary cardiac lymphoma is a rare, aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma that starts in the heart or pericardium (the sac surrounding the heart). It is often associated with immunocompromised states and tends to respond better to chemotherapy than sarcomas do.

Secondary (Metastatic) Heart Cancer

Cancer spreading to the heart from elsewhere is 20 to 40 times more common than primary heart cancer. Almost any cancer can metastasize to the heart, but the most frequent sources are lung cancer, breast cancer, esophageal cancer, melanoma, lymphoma, and leukemia. These metastases usually involve the pericardium, the outer lining of the heart, which can lead to a dangerous buildup of fluid called a malignant pericardial effusion. Treatment for metastatic heart cancer focuses on managing the primary cancer and alleviating cardiac complications to improve quality of life.

Symptoms and Signs of Heart Tumors

The symptoms of a heart tumor are notoriously nonspecific and often mimic more common heart conditions, which can lead to delayed diagnosis. Symptoms depend heavily on the tumor’s location, size, and whether it is benign or malignant. A tumor obstructing a valve or chamber will present differently than one that has invaded the heart muscle or caused pericardial fluid buildup.

Common symptoms include shortness of breath (especially when lying flat), fatigue, chest pain, palpitations or irregular heartbeats (arrhythmias), lightheadedness or fainting (syncope), and unexplained swelling in the legs or abdomen. A key characteristic of some benign tumors, like myxomas, is that symptoms may change with body position. Because these signs are so general, a high index of suspicion is needed for diagnosis, often involving imaging tests ordered for other suspected conditions.

Diagnosis and Detection Methods

Diagnosing heart cancer is a complex process that requires a combination of clinical evaluation and advanced imaging. There is no routine screening test for heart tumors. The journey to diagnosis often begins when a patient presents with unexplained heart failure symptoms, arrhythmias, or an embolic event. The following tools are critical in the diagnostic pathway:

- Echocardiogram (Cardiac Ultrasound): This is usually the first and most important test. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) provides a moving image of the heart and can identify the presence, location, size, and mobility of a mass. A transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), where the probe is passed down the esophagus, offers even clearer, more detailed images.

- Cardiac MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): This provides superior tissue characterization. It can help differentiate between a tumor, a blood clot, or normal tissue, and can assess the extent of invasion into the heart muscle and surrounding structures.

- Cardiac CT (Computed Tomography): Useful for evaluating the anatomy of the heart and great vessels, and for detecting calcifications within a tumor. It is also vital for checking if cancer has spread from the lungs to the heart.

- Biopsy: While imaging is suggestive, a definitive diagnosis of cancer requires a tissue sample. This can be obtained via a catheter-based procedure, during surgery, or sometimes through a pericardiocentesis (draining fluid from the pericardial sac) if malignant cells are present in the fluid.

- PET Scan: A positron emission tomography scan is used to determine if the tumor is metabolically active (a sign of cancer) and to stage the disease by looking for metastases elsewhere in the body.

Once a tumor is identified, a multidisciplinary team of cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, oncologists, and radiologists collaborates to interpret the findings and plan the appropriate treatment strategy.

Treatment Options and Prognosis

Treatment for heart cancer is highly individualized and depends on the tumor type, location, size, and whether it has spread. The rarity of the condition means there are no standardized treatment protocols, and care is often guided by case series and expert consensus. The primary goal for malignant primary tumors is complete surgical resection, but this is frequently challenging due to the tumor’s location and invasion of critical heart structures.

Surgery aims to remove as much of the tumor as possible while preserving heart function. In some cases, this may require complex reconstruction of the heart or even heart transplantation, though the latter is controversial due to the risk of cancer recurrence and the scarcity of donor organs. For tumors that cannot be fully removed, debulking surgery (removing a portion of the tumor) may be performed to relieve symptoms. Radiation therapy has a limited role due to the heart’s sensitivity to radiation damage, but newer techniques like proton beam therapy may offer more targeted options. Chemotherapy and targeted therapies are often used, particularly for sarcomas and lymphomas, either before surgery to shrink the tumor (neoadjuvant therapy) or after to kill remaining cells (adjuvant therapy).

The prognosis for primary malignant heart cancer, particularly sarcomas, is generally poor because of late diagnosis and aggressive tumor behavior. However, outcomes are improving with multimodal treatment approaches. For benign tumors like myxomas, surgical removal is usually curative. The prognosis for metastatic heart cancer is tied to the control of the primary cancer and the management of cardiac complications, such as pericardial effusions, which may be drained or treated with a pericardial window procedure to prevent recurrence.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you survive heart cancer?

Survival depends entirely on the type and stage of the tumor. Survival for aggressive primary sarcomas is often measured in months to a few years, even with treatment. For benign tumors like myxomas, complete surgical removal typically leads to a full recovery and normal life expectancy. Survival with metastatic heart cancer varies widely based on the primary cancer’s responsiveness to therapy.

What are the first signs of heart cancer?

There are no unique first signs. Initial symptoms are often vague and include shortness of breath, fatigue, irregular heartbeat, and swelling. These symptoms are far more likely to be caused by common conditions like coronary artery disease or heart failure than by a heart tumor.

How common is heart cancer?

Primary malignant heart cancer is extremely rare. Autopsy studies suggest primary cardiac tumors are found in only about 0.02% of people. In contrast, metastatic involvement of the heart is found in up to 20% of patients who die from other cancers, making it a more common clinical consideration in oncology.

Is a tumor in the heart always cancerous?

No. In fact, about three-quarters of primary heart tumors are benign. However, even benign tumors can cause serious, life-threatening complications by obstructing blood flow or breaking apart and causing strokes.

What causes heart cancer?

The causes of primary heart cancer are largely unknown. Unlike cancers linked to environmental factors like smoking or sun exposure, no clear risk factors have been established for most primary cardiac tumors. Some may have a genetic component, but this is not well understood due to the condition’s rarity.

While the diagnosis of a heart tumor is undoubtedly frightening, advances in cardiac imaging, surgical techniques, and medical oncology provide more options than ever before. A prompt, accurate diagnosis and a coordinated care plan from a specialized team are the cornerstones of managing this rare condition. Ongoing research into the molecular biology of these tumors may lead to more effective targeted therapies in the future, offering hope for improved outcomes.