From First Discovery to Future Research: The History of Alzheimers Disease

In November 1901, a 51-year-old woman named Auguste Deter was admitted to a Frankfurt asylum with a bewildering set of symptoms: profound memory loss, disorientation, paranoia, and unpredictable behavior. Her case, meticulously documented by a young German psychiatrist, would become the cornerstone of one of the most significant medical discoveries of the 20th century, yet it would take decades for its full impact to be understood. The story of the history of Alzheimers disease is not merely a timeline of medical milestones, but a profound narrative about how humanity grapples with the complexities of the brain, aging, and identity. It is a journey from a single case study to a global health crisis, marked by shifting definitions, scientific breakthroughs, and an evolving societal awareness that continues to shape research, care, and policy today, including how individuals plan for long-term health coverage. Understanding this history is crucial for appreciating the current landscape of diagnosis, treatment, and support for the millions affected.

The First Case and the Birth of a Concept (1901-1910)

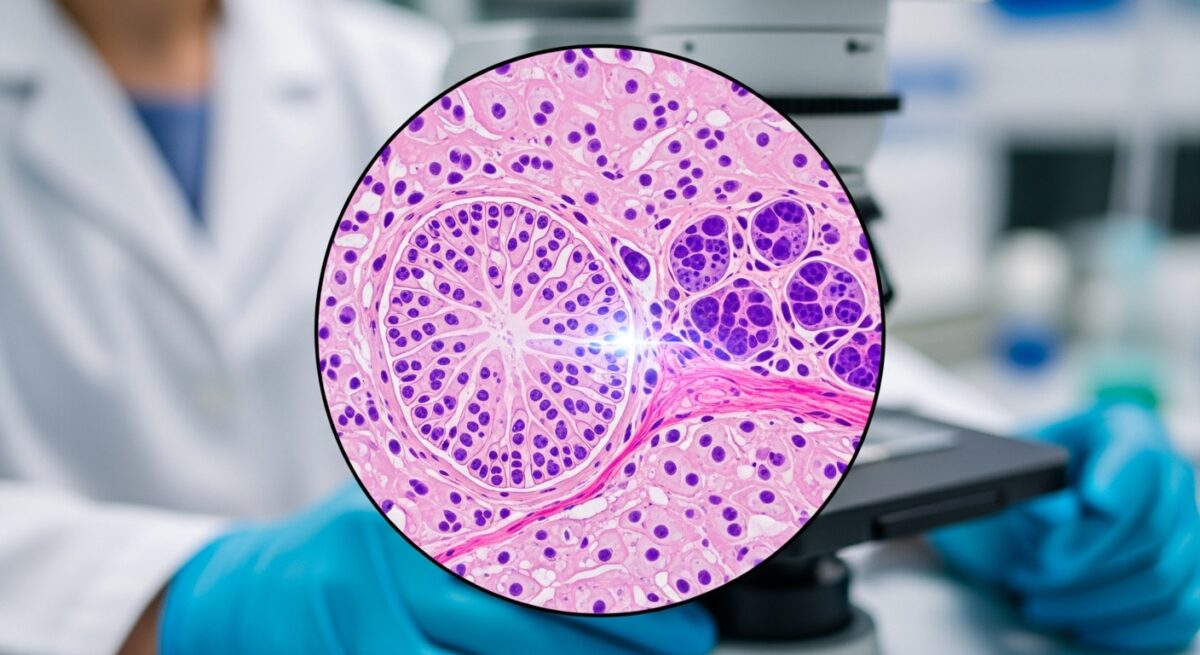

Dr. Alois Alzheimer, the psychiatrist who examined Auguste Deter, was a methodical clinician. He recorded her symptoms in detail, noting her confused speech, her inability to recall recent events, and her striking declaration, “I have lost myself.” When Deter died in 1906, Alzheimer, now working in Munich, had her brain sent to him for examination. Using newly developed silver-staining techniques, he made a startling discovery under the microscope. The brain tissue was riddled with two abnormal structures: dense clumps of cellular debris (later termed amyloid plaques) and tangled bundles of fibers inside nerve cells (neurofibrillary tangles). Alzheimer presented his findings at a psychiatry conference in 1907, describing “a peculiar severe disease process of the cerebral cortex.” His colleague, Emil Kraepelin, a leading psychiatrist who was classifying mental disorders, later named the condition “Alzheimer’s disease” in the 1910 edition of his influential textbook. Importantly, Kraepelin distinguished it from senile dementia, which was considered a normal part of aging, by highlighting its presenile (early-onset) nature. For decades, the condition remained a rare curiosity, diagnosed only in people under 65.

The Senility Paradigm and a Century of Stagnation (1910-1970s)

For much of the 20th century, the history of Alzheimers disease entered a period of relative obscurity and misconception. The prevailing medical and societal view was that significant cognitive decline was an inevitable consequence of old age, often dismissively labeled “senility” or “hardening of the arteries.” Alzheimer’s original discovery was largely confined to textbooks as a rare, early-onset condition. The profound suffering of older adults with dementia was frequently attributed to normal aging, leaving families without a clear diagnosis or support. This period saw little research investment or public discourse. However, a pivotal shift began in the 1960s and 1970s, driven by two key developments. First, researchers like Dr. Robert Katzman published a seminal 1976 editorial arguing that what was called “senile dementia” was pathologically identical to Alzheimer’s disease. He declared it a major public health issue, not a benign part of aging. Second, the electron microscope and biochemical advances allowed scientists to begin analyzing the composition of plaques and tangles, moving from mere observation to molecular inquiry. This era set the stage for Alzheimer’s to be redefined from a rare disorder to the common cause of dementia in the elderly.

The Modern Era: Molecular Revolution and Rising Awareness

The late 20th century witnessed an explosion in Alzheimer’s research, transforming it from a poorly understood condition into a major field of biomedical science. The 1980s marked a turning point with the identification of the core protein components of the brain’s pathological hallmarks. Beta-amyloid was isolated from plaques, and tau protein was identified as the main constituent of tangles. This molecular clarity allowed for more precise disease definitions. In 1984, standardized clinical criteria for diagnosing Alzheimer’s were established, creating a common language for doctors and researchers worldwide. Concurrently, public awareness surged. The formation of advocacy organizations, most notably the Alzheimer’s Association in the United States, played a crucial role in educating the public, supporting families, and lobbying for research funds. High-profile diagnoses, such as that of former President Ronald Reagan in 1994, brought the disease into the living rooms of millions, fostering a broader cultural understanding and reducing stigma. This period also saw the approval of the first class of drugs, cholinesterase inhibitors, in the 1990s, which offered symptomatic treatment, though not a cure.

Key Research Milestones from the 1990s to Present

The pace of discovery accelerated with genetic research. The identification of specific gene mutations (in the APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 genes) that cause rare, inherited forms of early-onset Alzheimer’s provided critical clues about disease mechanisms, particularly the overproduction of amyloid. For the more common late-onset form, the discovery of the APOE-e4 gene variant as a major risk factor was a landmark. Neuroimaging advanced dramatically, with the development of PET scans that could visualize amyloid plaques in living brains and MRI scans that could measure brain atrophy, moving diagnosis beyond mere clinical guesswork. Research began to reveal that the disease process likely begins decades before symptoms appear, leading to a paradigm shift towards prevention and early intervention. This modern era is characterized by an immense, global research effort to understand the complex cascade of events, from amyloid accumulation to tau spread, inflammation, and neuronal death. For a deeper look at the progression of symptoms, consider reading our guide on the three stages of Alzheimers disease.

Current Understanding, Challenges, and Future Directions

Today, Alzheimer’s disease is recognized as a progressive neurodegenerative disorder and the most common cause of dementia, affecting over 6 million Americans and tens of millions globally. The contemporary model is that of a long, preclinical phase followed by a gradual decline through mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to Alzheimer’s and then into dementia. The core pathological features defined by Alzheimer over a century ago remain central, but our understanding of their interplay and of other contributing factors (like vascular health and neuroinflammation) has deepened significantly. Despite this progress, formidable challenges persist. Definitive diagnosis still requires postmortem brain examination, though clinical and biomarker-based diagnoses are highly accurate. Available medications manage symptoms but do not halt progression, a source of great frustration. The recent, controversial approval of disease-modifying therapies targeting amyloid plaques represents a new chapter, promising to slow decline but also raising questions about efficacy, cost, and access. The history of Alzheimers disease now points towards several critical future directions. Early detection through blood-based biomarkers is a major frontier. Lifestyle intervention studies suggest that managing cardiovascular risk factors (like hypertension and diabetes) may reduce dementia risk. Research is also increasingly focused on resilience, exploring why some brains with pathology show no symptoms. You can explore current approaches in our overview of Alzheimers disease treatment options and support strategies.

The financial and caregiving burden of Alzheimer’s is immense, making proactive health and financial planning essential. For many seniors, understanding Medicare coverage for cognitive assessments, diagnostic tests, and potential therapies is a critical part of this planning. As research advances, ensuring equitable access to new diagnostics and treatments will be a major societal challenge. For comprehensive information on how health insurance intersects with managing long-term conditions, Read full article.

Frequently Asked Questions

Was Alzheimer’s disease less common in the past?

It is difficult to know for certain, as diagnostic criteria were absent and symptoms were often attributed to normal aging. Increased life expectancy is the single biggest risk factor, so as populations age, the prevalence rises. Better diagnosis and awareness also contribute to higher reported numbers today.

What was the biggest misconception about Alzheimer’s in history?

The most damaging misconception was that severe memory loss and confusion were an inevitable, untreatable part of getting old. This “senility” paradigm prevented research, marginalized patients, and left families without support for most of the 20th century.

How has the definition of Alzheimer’s disease changed?

It evolved from a rare, presenile condition to the common cause of dementia in older adults. Today, it is defined by its underlying biology (plaques and tangles) rather than just age of onset, and it is recognized as a process that begins long before symptoms appear.

Why is the discovery of the first case still important?

Auguste Deter’s case provided the first clear clinicopathological correlation: linking specific, observed symptoms (clinical presentation) with distinct physical changes in the brain (pathology). This established Alzheimer’s as a unique biological disease, not just a behavioral syndrome.

What are the most promising areas of current research?

Key areas include: blood tests for early detection, understanding the role of tau and inflammation alongside amyloid, lifestyle and cardiovascular risk interventions for prevention, and developing more effective disease-modifying and symptomatic therapies. For individuals and families, recognizing early signs is crucial. Learn more about recognizing Alzheimers disease symptoms and early signs.

The history of Alzheimers disease is a testament to the slow, often non-linear progress of science and societal change. From Alois Alzheimer’s microscope to today’s global research initiatives, the journey reflects our relentless pursuit to understand the human mind. While a cure remains elusive, each chapter in this history builds a foundation for better care, greater compassion, and the hope that future generations will face this disease with far more power and knowledge than we have today. The story is still being written, and its next chapters depend on continued research, advocacy, and support.