Critical Facts About Alzheimer’s Disease: Risk, Symptoms, and Care

Alzheimer’s disease is more than just simple forgetfulness, it is a progressive neurological disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills, and, eventually, the ability to carry out the simplest tasks. For the millions of individuals and families navigating an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, understanding the fundamental facts about this condition is the first step toward effective management, planning, and finding support. Beyond the headlines, a clear grasp of the causes, progression, risk factors, and current treatment landscape empowers caregivers and patients alike. This article delves into the essential and often surprising facts about Alzheimer’s disease, separating myth from reality and providing a foundation for informed decisions about health and future care.

Understanding Alzheimer’s Disease: More Than Just Memory Loss

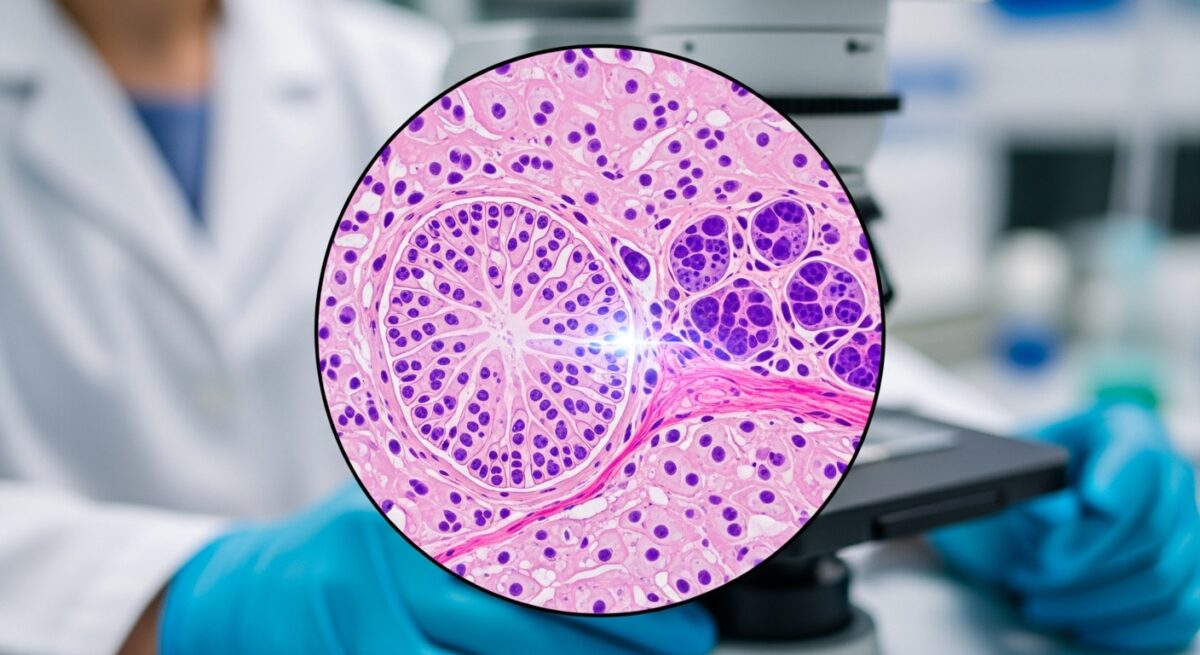

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia, a general term for a decline in cognitive ability severe enough to interfere with daily life. It accounts for an estimated 60-80% of dementia cases. The disease is named after Dr. Alois Alzheimer, who in 1906 noticed changes in the brain tissue of a woman who had died of an unusual mental illness. Her symptoms included memory loss, language problems, and unpredictable behavior. Upon examination, Dr. Alzheimer found abnormal clumps (now called amyloid plaques) and tangled bundles of fibers (now called neurofibrillary, or tau, tangles). These plaques and tangles in the brain are still considered the hallmark pathologies of Alzheimer’s disease. They are thought to block communication between nerve cells and disrupt the processes that cells need to survive. The destruction and death of nerve cells cause memory failure, personality changes, and problems carrying out daily activities.

It is critical to differentiate between normal age-related cognitive changes and the signs of Alzheimer’s. While occasional lapses in memory, such as misplacing keys or forgetting a name, are common with aging, Alzheimer’s-related memory loss is persistent and worsens over time, affecting the ability to function at work or at home. For a detailed exploration of these distinctions, our resource on recognizing Alzheimer’s disease symptoms provides a comprehensive guide to early signs.

Key Risk Factors and Potential Causes

The exact causes of Alzheimer’s disease are not fully understood, but scientists believe it results from a combination of genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors that affect the brain over time. Age is the greatest known risk factor. The likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s doubles about every five years after age 65. However, Alzheimer’s is not a normal part of aging, and it can also affect younger people in what is known as early-onset Alzheimer’s, which can appear in individuals in their 40s and 50s.

Family history and genetics play a role. Those who have a parent, brother, or sister with Alzheimer’s are more likely to develop the disease. Specific genes have been identified that increase risk. The APOE-e4 gene is the strongest risk gene for late-onset Alzheimer’s. Inheriting one copy from a parent increases risk, while inheriting two copies significantly raises it, though not everyone with the gene develops the disease. Research also points to a strong link between serious head injuries and future risk of Alzheimer’s. Furthermore, growing evidence suggests that heart health is closely tied to brain health. The brain is nourished by one of the body’s richest networks of blood vessels, and damage to blood vessels in the brain can contribute to Alzheimer’s. Conditions that damage the heart or blood vessels, including heart disease, diabetes, stroke, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol, may increase the risk.

The Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease Progression

Alzheimer’s disease typically progresses slowly in three general stages: mild (early-stage), moderate (middle-stage), and severe (late-stage). Understanding these stages helps in anticipating needs and planning for care. In the mild stage, a person may function independently but starts experiencing memory lapses, such as forgetting familiar words or the location of everyday objects. They may have trouble with planning, organizing, or managing finances. Personality changes, like becoming withdrawn or irritable in socially or mentally challenging situations, can occur.

The moderate stage is often the longest and can last for many years. As the disease progresses, the individual will require a greater level of care. Damage to nerve cells in the brain can make it difficult to express thoughts and perform routine tasks. They may become confused about where they are or what day it is. Significant personality changes are more likely, including suspiciousness, delusions, or compulsive, repetitive behavior. In the severe stage, individuals lose the ability to respond to their environment, carry on a conversation, and, eventually, control movement. Memory and cognitive skills continue to worsen, and extensive help with daily activities is required. They may have difficulty swallowing, which increases the risk of malnutrition, pneumonia, and infections. A deeper look into this progression can be found in our simple guide to the three stages of Alzheimer’s disease, which is an invaluable resource for caregivers.

To clarify common points of confusion, here are some key facts about Alzheimer’s disease progression:

- Progression varies greatly from person to person, with an average life span of 4 to 8 years after diagnosis, but some live as long as 20 years.

- Alzheimer’s is fatal. It is the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States, and the fifth-leading cause for those aged 65 and older.

- While there is no cure, treatments exist that can temporarily slow the worsening of symptoms and improve quality of life.

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Current Research

There is no single test for Alzheimer’s disease. Doctors use a variety of approaches and tools to help make a diagnosis. These include obtaining a detailed medical history, conducting mental status tests, performing physical and neurological exams, and utilizing brain imaging (such as MRI or CT scans) to rule out other causes. Newer imaging technologies and cerebrospinal fluid analysis can sometimes detect the biological markers of the disease, but these are typically used in research settings or complex cases.

While no treatment stops or reverses the underlying disease process, several medications can help lessen or stabilize symptoms for a limited time. The mainstays of treatment are cholinesterase inhibitors (like donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine) for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s, and memantine, an NMDA receptor antagonist, for moderate to severe stages. These drugs work by regulating neurotransmitters in the brain. Non-drug approaches are equally critical. Creating a safe and supportive environment, establishing routines, and using memory aids can help manage behavioral symptoms and maintain functional abilities. For a comprehensive overview of medical and support strategies, our article on Alzheimer’s disease treatment options offers detailed guidance.

Research into Alzheimer’s is more active than ever, focusing on several promising avenues. Scientists are investigating the role of beta-amyloid and tau proteins with the goal of developing therapies that prevent, slow, or remove these abnormalities. Inflammation and insulin resistance in the brain are also areas of intense study. Furthermore, lifestyle interventions, such as the combination of diet and exercise, are being rigorously tested for their potential to prevent cognitive decline. Clinical trials are essential for advancing our understanding, and many patients and families choose to participate to contribute to future breakthroughs.

Caregiving, Support, and Planning for the Future

Caring for a person with Alzheimer’s disease is physically and emotionally demanding. The role of a caregiver often involves assisting with daily activities, managing behavioral changes, ensuring safety, and coordinating medical care. It is vital for caregivers to seek support for themselves to prevent burnout. This can include joining a support group, utilizing respite care services, and asking for help from family and friends.

Financial and legal planning is a crucial, though difficult, step that should be addressed soon after a diagnosis. This includes establishing power of attorney for finances and healthcare, discussing long-term care wishes, and understanding the costs associated with care. Medicare, the federal health insurance program for people 65 and older, covers some costs associated with Alzheimer’s, such as inpatient hospital care, doctor visits, and up to 100 days of skilled nursing facility care per benefit period following a hospitalization. However, it does not cover long-term custodial care, which is often the greatest expense. Medicaid may provide coverage for long-term care for those who meet financial eligibility requirements. Understanding these complex benefits is essential. For more detailed information on navigating insurance and care options, you can Read full article on related health insurance topics.

Frequently Asked Questions About Alzheimer’s Disease

Can Alzheimer’s disease be prevented?

There is no proven way to prevent Alzheimer’s, but evidence suggests that adopting a heart-healthy lifestyle may help reduce risk. This includes regular physical activity, a diet rich in fruits and vegetables (such as the Mediterranean or MIND diets), managing cardiovascular risk factors (like hypertension and diabetes), staying socially and mentally active, and avoiding smoking and excessive alcohol consumption.

What is the difference between dementia and Alzheimer’s?

Dementia is an umbrella term for a set of symptoms that includes impaired thinking and memory. Alzheimer’s disease is a specific, and the most common, brain disease that causes these dementia symptoms. Other types of dementia include vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and frontotemporal disorders.

Is Alzheimer’s hereditary?

Family history increases risk, but in most cases, it is not purely hereditary. Early-onset Alzheimer’s, which is rare, is more strongly linked to specific genetic mutations. For the more common late-onset Alzheimer’s, having the APOE-e4 gene increases risk but does not guarantee the disease will develop.

How can I communicate effectively with someone who has Alzheimer’s?

Use simple words and short sentences. Speak in a calm, reassuring tone. Maintain eye contact and minimize distractions. Be patient and give them time to respond. Avoid arguing or correcting them if they are confused about facts.

Ultimately, knowledge is a powerful tool in the face of Alzheimer’s disease. By separating fact from fiction, understanding the progression, and knowing where to find resources and support, individuals and families can move from a place of fear to one of preparedness and empowerment. While the journey is undeniably challenging, advancements in research continue to provide hope for better treatments and, one day, a cure. Staying informed through reputable sources, connecting with support networks, and working closely with healthcare professionals are the best strategies for managing life with Alzheimer’s today.