Ampullary Cancer: Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options

Ampullary cancer is a rare but significant malignancy that arises from the ampulla of Vater, a small but crucial structure where the bile duct and pancreatic duct meet and empty into the small intestine. Due to its location, this cancer often causes symptoms like jaundice relatively early, which can lead to earlier diagnosis compared to other pancreatic or biliary tract cancers. However, its rarity means patients and even some healthcare providers may be less familiar with its specific presentation and management. Understanding the nuances of ampullary cancer, from its initial signs to complex treatment pathways, is essential for navigating this diagnosis and making informed decisions about care.

What Is Ampullary Cancer?

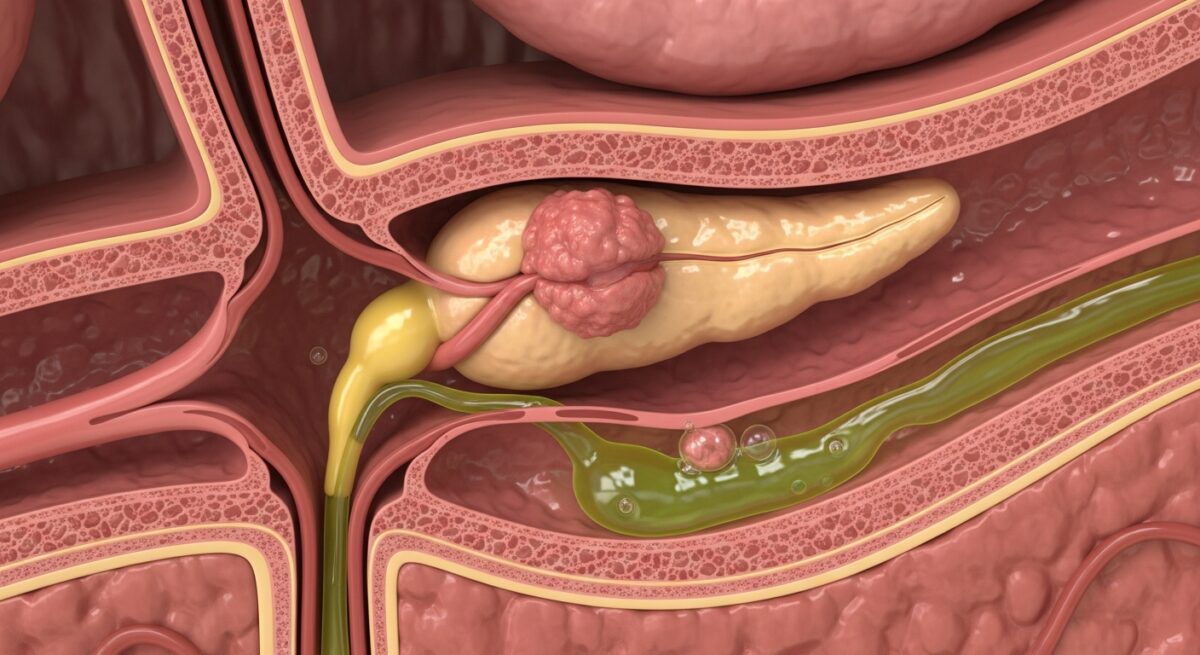

Ampullary cancer, also known as carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater, originates in the ampulla. This is the point where the common bile duct (carrying bile from the liver) and the main pancreatic duct (carrying digestive enzymes from the pancreas) join before releasing their contents into the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine. The tumor develops from the glandular cells lining this ampullary region. Because of its origin at a major junction, even a small tumor can block the flow of both bile and pancreatic juices, leading to noticeable symptoms such as yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice), pale stools, and dark urine. This obstructive effect is often what brings the cancer to medical attention.

It is critical to distinguish ampullary cancer from other periampullary cancers, which arise in the surrounding structures: the head of the pancreas, the distal common bile duct, or the duodenum itself. While these cancers are geographically close and can cause similar symptoms, they are biologically distinct. Ampullary cancers generally have a more favorable prognosis than pancreatic cancer, for instance, partly because of earlier symptom onset leading to earlier-stage diagnosis. The tumor’s behavior and treatment response can also vary based on its specific cellular subtype, which is determined through pathology after biopsy or surgical resection.

Causes and Risk Factors

The exact cause of ampullary cancer is not fully understood, as is the case with many rare cancers. However, several risk factors and associated conditions have been identified. Most cases appear to be sporadic, meaning they occur by chance without a clear inherited link. However, a significant minority of cases are associated with specific genetic syndromes that predispose individuals to gastrointestinal cancers.

One of the most well-established genetic links is with Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP). Individuals with FAP develop hundreds to thousands of polyps in their colon and also have a markedly increased lifetime risk of developing ampullary cancer, often from adenomas (pre-cancerous polyps) in the ampulla. Other hereditary conditions, such as Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer, HNPCC) and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, also confer an elevated risk. Beyond genetics, demographic factors play a role. The risk increases with age, with most patients diagnosed in their 60s and 70s. There may be a slight male predominance. Some studies suggest a link with smoking and obesity, though the evidence is not as strong as for pancreatic cancer. Chronic inflammation in the area, such as from gallstones or chronic pancreatitis, is also considered a potential contributing factor.

Symptoms and Early Signs

The symptoms of ampullary cancer are primarily caused by the tumor obstructing the bile duct or pancreatic duct. This obstruction prevents digestive fluids from reaching the intestine and causes them to back up into the liver and bloodstream. The most common and often the first symptom is painless jaundice. This presents as a yellowing of the skin and the whites of the eyes. It is frequently accompanied by other signs of biliary obstruction: dark brown urine (from bilirubin excreted by the kidneys), pale or clay-colored stools (due to a lack of bile pigments), and generalized itching (pruritus) caused by bile salts depositing in the skin.

As the cancer progresses or due to associated inflammation, other symptoms may develop. These can include unexplained weight loss, loss of appetite, abdominal pain or discomfort (often in the upper abdomen), nausea, and vomiting. Back pain is less common but can occur. Some patients may experience episodes of pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas) if the pancreatic duct becomes blocked. A rare but notable symptom is gastrointestinal bleeding, which can manifest as black, tarry stools (melena) or even visible blood if the tumor erodes into a blood vessel. It is important to note that while jaundice is a hallmark, its presence does not confirm ampullary cancer, as it can be caused by gallstones, other tumors, or liver disease. However, the onset of painless jaundice, especially in an older adult, always warrants prompt and thorough medical investigation.

Diagnostic Process and Staging

Diagnosing ampullary cancer requires a multi-step approach that begins with a detailed medical history and physical exam, focusing on signs of jaundice and abdominal tenderness. The diagnostic journey typically involves a combination of blood tests, advanced imaging, and direct visualization with tissue sampling.

Initial blood tests often reveal a pattern consistent with obstructive jaundice: elevated levels of bilirubin and liver enzymes like alkaline phosphatase. Tumor markers, specifically CA 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), may be elevated, but they are not specific for ampullary cancer and can be raised in other conditions. Imaging is a cornerstone of diagnosis. An abdominal ultrasound is often the first test to look for bile duct dilation. However, the definitive imaging usually involves a cross-sectional scan like a computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast or a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). These tests provide detailed pictures of the tumor, its size, its local invasion, and whether it has spread to nearby lymph nodes or distant organs like the liver.

The gold standard for diagnosis and local staging is an endoscopic procedure called an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). During an ERCP, a gastroenterologist passes a flexible tube with a camera down the throat, through the stomach, and into the duodenum to directly view the ampulla. If a tumor is seen, biopsies can be taken. The ERCP also allows for therapeutic interventions, such as placing a stent to relieve bile duct obstruction and alleviate jaundice before surgery. Another endoscopic technique, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), uses an ultrasound probe on the endoscope to get extremely detailed images of the tumor’s depth and involvement of local structures; EUS also allows for fine-needle aspiration (FNA) to obtain tissue samples from the tumor or suspicious lymph nodes.

Once a diagnosis is confirmed, the cancer is staged. Staging determines the extent of the disease and guides treatment. The most common system used is the TNM (Tumor, Node, Metastasis) system:

- T (Tumor): Describes the size and depth of invasion of the primary tumor (e.g., confined to the ampulla, invading the duodenal wall, or invading the pancreas).

- N (Node): Indicates whether cancer cells have spread to regional lymph nodes.

- M (Metastasis): Signifies whether the cancer has spread (metastasized) to distant organs, such as the liver or lungs.

Staging is typically finalized after surgical resection, when the entire tumor and lymph nodes can be examined by a pathologist. Accurate staging is crucial for predicting prognosis and planning adjuvant therapy.

Treatment Strategies and Approaches

The treatment plan for ampullary cancer is highly individualized, depending on the stage of the disease at diagnosis, the patient’s overall health and age, and the specific biological characteristics of the tumor. A multidisciplinary team, including surgical oncologists, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, gastroenterologists, and pathologists, collaborates to recommend the best course of action.

For localized, resectable cancer (Stages I, II, and some Stage III), surgical removal is the only potentially curative treatment. The standard operation is a pancreaticoduodenectomy, commonly known as a Whipple procedure. This is a complex surgery that involves removing the head of the pancreas, the entire duodenum, the gallbladder, part of the common bile duct, and sometimes part of the stomach. The surgeon then reconstructs the digestive tract by connecting the remaining pancreas, bile duct, and stomach to the small intestine. In select cases where the tumor is very small and favorable, a less extensive local resection (ampullectomy) may be performed endoscopically or surgically, but the Whipple remains the standard for most cases to ensure complete removal and adequate lymph node sampling.

After surgery, the role of additional (adjuvant) therapy is determined by the pathology report. If the tumor was high-grade, had lymph node involvement, or had positive margins, adjuvant chemotherapy (drugs like gemcitabine, capecitabine, or a combination like FOLFIRINOX) is often recommended to reduce the risk of recurrence. Radiation therapy, sometimes given concurrently with chemotherapy (chemoradiation), may also be considered in certain high-risk scenarios.

For patients with locally advanced, unresectable disease (where the tumor involves major blood vessels and cannot be safely removed) or metastatic disease (Stage IV), cure is not typically possible. Treatment then focuses on controlling the cancer, relieving symptoms, and maintaining quality of life. This involves systemic therapies like chemotherapy and, increasingly, targeted therapies or immunotherapy if the tumor has specific genetic markers. Palliative procedures, such as endoscopic stenting during an ERCP to keep the bile duct open, are essential for managing jaundice and preventing complications like infection (cholangitis). Pain management and nutritional support are also critical components of care for advanced disease.

Prognosis and Follow-Up Care

The prognosis for ampullary cancer is generally more favorable than for other periampullary cancers, particularly pancreatic cancer. This is largely due to the earlier presentation with obstructive symptoms. The overall 5-year survival rate after a curative-intent Whipple procedure can range from 30% to 60% or higher, heavily influenced by the stage at surgery. Tumors that are confined to the ampulla (T1) with no lymph node spread have the best outcomes, with 5-year survival rates often exceeding 70%. The presence of lymph node metastasis significantly reduces survival rates, underscoring the importance of early detection and complete surgical resection.

Long-term follow-up after treatment is essential. This involves regular check-ups with physical exams, blood tests (including liver function tests and tumor markers like CA 19-9), and periodic imaging (CT scans) to monitor for any signs of recurrence. Patients also need monitoring for and management of long-term effects from surgery, such as diabetes (if a significant portion of the pancreas was removed), digestive issues like malabsorption or dumping syndrome, and nutritional deficiencies. Support from dietitians, diabetes educators, and support groups can be invaluable for recovery and long-term health maintenance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is ampullary cancer the same as pancreatic cancer?

No, they are distinct cancers. Ampullary cancer starts in the ampulla of Vater, while pancreatic cancer starts in the pancreas itself. They are often grouped as “periampullary” cancers due to their proximity, but they have different behaviors, treatments, and prognoses.

What is the main symptom I should watch for?

The most common and telling early symptom is painless jaundice: yellowing of the skin and eyes, often with dark urine and pale stools. Any new onset of jaundice requires immediate medical evaluation.

Is the Whipple procedure the only surgical option?

For most patients, yes, the Whipple (pancreaticoduodenectomy) is the standard curative surgery. In very rare, select cases of very small, early-stage tumors, a local ampullectomy might be considered, but the Whipple provides the most comprehensive removal and lymph node assessment.

Can ampullary cancer be inherited?

Most cases are not inherited. However, a significant minority (around 5-10%) are associated with inherited genetic syndromes like Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP). A family history of colon polyps or multiple cancers should be discussed with your doctor.

What are the latest advances in treatment?

Research is ongoing into more effective chemotherapy regimens, targeted therapies that attack specific genetic mutations in cancer cells, and immunotherapies. Molecular profiling of the tumor after biopsy or surgery is becoming more common to identify potential targets for these newer treatments.

Navigating a diagnosis of ampullary cancer is challenging, but advances in diagnostic techniques, surgical precision, and systemic therapies continue to improve outcomes. Early recognition of symptoms like jaundice leads to timely intervention, which remains the single most important factor for a successful result. With a coordinated, multidisciplinary approach to care, patients can access the full spectrum of treatment options tailored to their specific condition, offering the best possible path forward.