Understanding Alzheimer’s Disease 2026: A Guide to Symptoms and Causes

Imagine misplacing your keys, then forgetting what keys are for. This is the stark reality of Alzheimer’s disease, the most common cause of dementia, a progressive neurological disorder that erodes memory, thinking, and the very ability to perform simple tasks. It is not a normal part of aging, but a devastating illness caused by complex brain changes that lead to cell damage and death. Understanding what Alzheimer’s disease is, from its earliest biological whispers to its profound impact on daily life, is the first step toward compassion, effective care planning, and supporting the ongoing search for a cure. For millions of families and individuals navigating this journey, clarity about the condition is essential for making informed decisions about health, lifestyle, and long-term care, including how Medicare and other plans can support the path ahead.

The Defining Characteristics of Alzheimer’s Disease

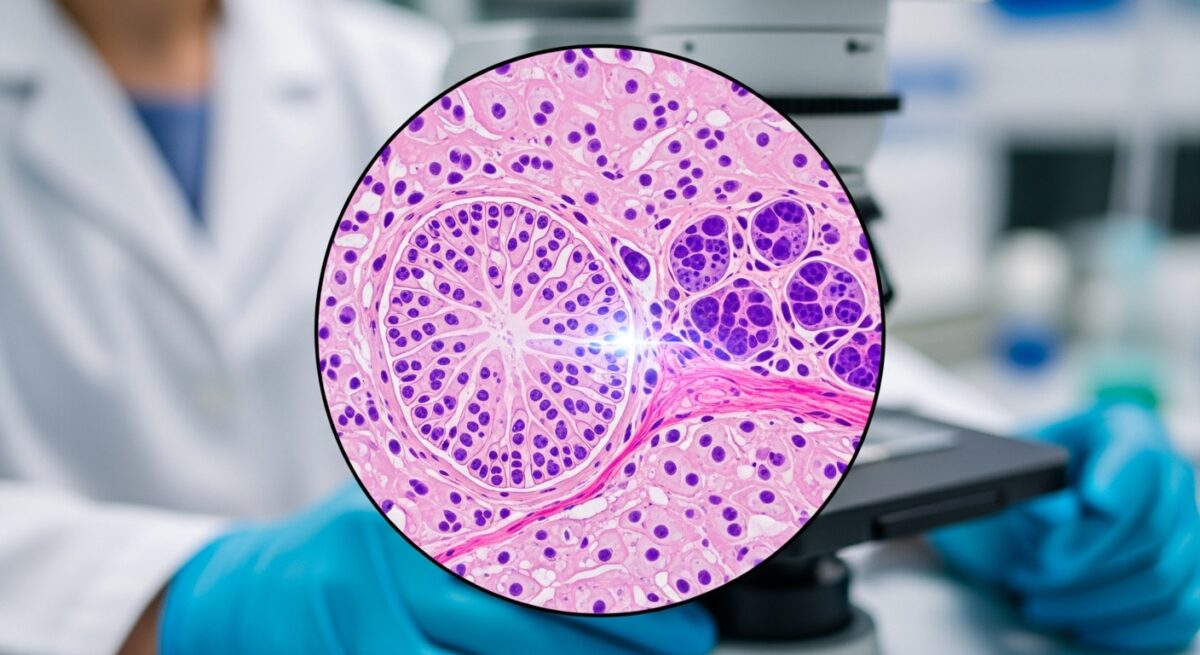

Alzheimer’s disease is a specific, irreversible neurodegenerative disorder. At its core, it is characterized by the accumulation of two abnormal protein structures in the brain: amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Amyloid plaques are sticky clumps of protein fragments that build up between nerve cells, potentially disrupting cell communication. Neurofibrillary tangles are twisted fibers of a protein called tau that form inside brain cells, blocking the transport of nutrients and other essential molecules, leading to cell death. This biological onslaught primarily begins in the hippocampus, the brain’s center for learning and memory, which explains why memory loss is typically the first and most prominent symptom. As the disease progresses, it spreads to other cortical areas, impairing language, reasoning, social behavior, and, ultimately, the brain’s ability to control bodily functions.

The distinction between Alzheimer’s and general dementia is crucial. Dementia is an umbrella term for a set of symptoms severe enough to interfere with daily life, including memory loss and cognitive decline. Alzheimer’s disease accounts for 60-80% of all dementia cases. Other types include vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and frontotemporal dementia. While symptoms may overlap, each has different underlying causes and progression patterns. A definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer’s can only be confirmed by examining brain tissue after death, but clinicians use comprehensive assessments to reach a diagnosis with high accuracy during life. This process involves medical history reviews, mental status tests, neurological exams, and brain imaging to rule out other conditions.

Recognizing the Stages and Symptoms

Alzheimer’s disease progresses in a generally predictable pattern, though the rate varies significantly from person to person. The journey is often described in three broad stages: early (mild), middle (moderate), and late (severe). In the early stage, symptoms may be subtle and mistaken for normal aging. An individual might experience mild memory lapses, such as forgetting familiar words or the location of everyday objects. They may have trouble planning or organizing, and slight changes in personality, like increased anxiety or withdrawal in social situations, can occur. Crucially, the person often remains largely independent but may start to compensate for these challenges.

The moderate stage is typically the longest and brings a more pronounced decline. Memory loss deepens, often extending to personal history. Confusion about time and place increases, and individuals may have difficulty recognizing family and friends. They may exhibit significant personality and behavioral changes, including suspiciousness, agitation, or repetitive behaviors. This stage often requires substantial supervision and assistance with daily activities like dressing and bathing. In the severe or late stage, individuals lose the ability to respond to their environment, carry on a conversation, and, eventually, control movement. They need round-the-clock care for all activities of daily living. Communication becomes extremely limited, and physical abilities like walking, sitting, and swallowing deteriorate, making the individual vulnerable to infections, especially pneumonia.

Key Warning Signs Different from Normal Aging

It’s vital to distinguish between typical age-related changes and potential signs of Alzheimer’s. Not every memory lapse is a cause for alarm, but a pattern of decline is. Common early warning signs include memory loss that disrupts daily life, such as asking for the same information repeatedly or relying heavily on memory aids. Challenges in solving familiar problems, like managing monthly bills, or difficulty completing routine tasks at home or work are significant indicators. Other red flags include confusion with time or place, new problems with words in speaking or writing, misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps, decreased or poor judgment, withdrawal from work or social activities, and changes in mood and personality, such as becoming confused, suspicious, depressed, fearful, or anxious.

Unraveling the Causes and Risk Factors

The exact cause of Alzheimer’s disease is not fully understood, but it is widely believed to result from a combination of genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors that affect the brain over time. In less than 1% of cases, specific genetic differences virtually guarantee a person will develop Alzheimer’s, often with an early onset before age 65. For the vast majority of late-onset cases, the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene is a key risk factor. Having the APOE-e4 variant increases risk, but it does not mean Alzheimer’s is certain. Research is intensely focused on how this and other genes interact with lifestyle factors.

Beyond genetics, several non-modifiable and modifiable risk factors have been identified. The greatest known risk factor is increasing age; the majority of people with Alzheimer’s are 65 and older. Family history and having a first-degree relative with the condition also increases risk. Importantly, a growing body of evidence points to heart health being intimately linked to brain health. Conditions that damage the heart and blood vessels, such as heart disease, diabetes, stroke, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol, may increase Alzheimer’s risk. Other modifiable factors include a history of traumatic brain injury, social isolation, and consistently poor sleep patterns. While risk factors cannot be eliminated, managing cardiovascular health through diet, exercise, and controlling chronic conditions is considered one of the most promising ways to potentially reduce overall risk.

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management Approaches

There is no single test for Alzheimer’s. Diagnosis involves a comprehensive evaluation to rule out other potential causes of dementia symptoms, such as vitamin deficiencies, thyroid problems, or depression. The process usually includes a detailed medical history, mental status testing to assess memory and thinking skills, physical and neurological exams, and brain imaging (MRI or CT scans) to look for brain shrinkage or rule out tumors or strokes. In some cases, newer PET scans or cerebrospinal fluid analysis can help detect amyloid pathology. An early and accurate diagnosis is beneficial, as it allows individuals and families to plan for the future, access treatments and support services, and address safety concerns.

While there is no cure for Alzheimer’s, several treatments can help manage symptoms. Current FDA-approved medications fall into two categories: cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine) for mild to moderate stages, and memantine for moderate to severe stages. These drugs may help lessen or stabilize symptoms for a limited time by regulating neurotransmitters in the brain. In recent years, a new class of drugs, amyloid-beta-directed antibodies, has received accelerated approval. These drugs, such as lecanemab, target and remove amyloid plaques from the brain and represent the first treatments to address the underlying biology of the disease, showing modest slowing of cognitive decline in clinical trials. It is critical to understand that these are not cures and come with significant risks, including brain swelling and bleeding.

Non-drug strategies are fundamental to comprehensive care. Creating a safe and supportive environment, establishing routines, and using memory aids can help maintain function and reduce anxiety. Behavioral interventions can address agitation, sleep disturbances, and depression. A holistic management plan often includes:

- Structured daily routines to provide predictability and reduce confusion.

- Cognitive stimulation through simple, enjoyable activities.

- Physical activity tailored to ability, which may help improve mood and maintain physical health.

- Nutritional support to ensure adequate hydration and prevent weight loss.

- Caregiver support and education, which is essential for the well-being of both the individual and their family.

Planning for long-term care is a critical component. As the disease progresses, care needs escalate, often requiring home health aides, adult day programs, or residential memory care facilities. Understanding coverage options through health insurance, long-term care insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare is vital. For eligible individuals aged 65 and older, Medicare Part A may cover inpatient hospital care, some skilled nursing facility care, hospice care, and some home health care. Medicare Part B covers certain doctors’ services, outpatient care, and some preventive services, including the annual wellness visit which includes a cognitive assessment. Medicare Advantage plans (Part C) offered by private insurers must provide at least the same coverage as Original Medicare and often include additional benefits, which may include care coordination programs or support services for chronic conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions

How is Alzheimer’s disease different from normal forgetfulness?

Normal age-related forgetfulness might involve briefly forgetting a name but recalling it later. Alzheimer’s-related memory loss is persistent and progressive, disrupting daily life. For example, forgetting how to drive to a familiar location or how to use a common appliance goes beyond typical forgetfulness.

Can Alzheimer’s disease be prevented?

There is no proven way to prevent Alzheimer’s. However, strong evidence suggests that managing cardiovascular risk factors may reduce overall risk or delay onset. This includes regular physical exercise, a heart-healthy diet like the Mediterranean diet, staying socially and mentally active, managing stress, and treating conditions like hypertension and diabetes.

What is the life expectancy after an Alzheimer’s diagnosis?

On average, a person with Alzheimer’s lives four to eight years after diagnosis, but survival can range from three to 20 years, depending on age at diagnosis, other health conditions, and the rate of progression. The disease itself is ultimately fatal, as brain damage leads to the failure of essential bodily functions.

Does Medicare cover the cost of Alzheimer’s care?

Medicare covers medically necessary services like doctor visits, hospital stays, and some home health or skilled nursing care, but it does not cover long-term custodial care (help with daily activities like bathing and dressing) in a nursing home or memory care facility. Some Medicare Advantage plans may offer supplemental benefits for support services. Coverage for new Alzheimer’s treatments like lecanemab is evolving and often requires meeting specific criteria and receiving the drug through a registered provider.

Are there any promising developments in Alzheimer’s research?

Research is advancing on multiple fronts. Beyond new anti-amyloid treatments, scientists are investigating therapies targeting tau protein, inflammation, and insulin resistance in the brain. Advances in early detection through blood tests and digital biomarkers are also a major focus, hoping to identify the disease years before symptoms appear, when interventions might be most effective.

Navigating an Alzheimer’s diagnosis is a profound challenge for individuals and families, marked by uncertainty and a changing landscape of needs. Yet, within that challenge lies the power of knowledge and preparation. Understanding the biological underpinnings, recognizing the trajectory of symptoms, and proactively exploring management and care options can provide a crucial sense of agency. From leveraging available medical treatments and non-pharmacological strategies to planning for the financial and caregiving realities, informed action is the cornerstone of maintaining quality of life and dignity for as long as possible. Continued support for research offers hope for more effective future interventions, while community resources and caregiver support remain indispensable pillars of care today.

For personalized guidance on care planning and resources for Alzheimer’s disease, call 📞833-203-6742 or visit Understand Staged Care to speak with a specialist.